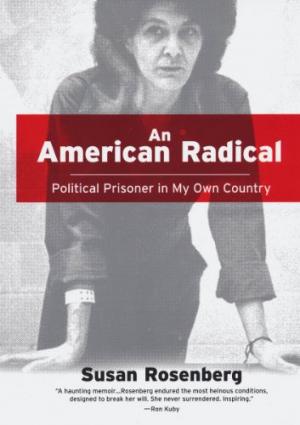

An American Radical: Political Prisoner in My Own Country

Twenty-seven years ago, activists Susan Rosenberg and Timothy Blunk were caught transporting explosives to a New Jersey storage facility. Although the pair had no immediate plans to use the incendiary materials, they—and their comrades in the May 19 Communist Party—were stockpiling them for a revolution they believed was imminent.

Rosenberg’s searing memoir, An American Radical—a chronicle of sixteen years spent in four U.S. prisons—doesn’t spend much time analyzing the reasoning behind this idea. Instead, it focuses on the government’s treatment of incarcerated political opponents. Rosenberg describes heinous abuses, from 24/7 surveillance, to sleep deprivation, overcrowding, medical neglect, and outright nastiness by prison employees. Rehabilitation? Rosenberg scoffs. The High Security Units in which political prisoners are kept, she writes, “seek to reduce prisoners to a state of submission essential for their ideological conversion. That failing, the next objective is to reduce them to a state of psychological incompetence sufficient to neutralize them as efficient self-directing antagonists. That failing, the only alternative is to destroy them, preferably by making them desperate enough to destroy themselves.”

Nowhere is this clearer than in a chapter entitled “My Father.” In it, Rosenberg offers a painful reflection on her attempt to visit her terminally ill dad. “A prisoner may request a two-hour deathbed visit or attendance at the funeral,” she writes. “A prisoner may not request both. If granted permission for the visit, the prisoner must pay the salary of the accompanying security detail.” The machinations that followed Rosenberg’s request are mind-boggling. Despite appeals from a host of people—including her lawyers, a family rabbi, and Congressman Jerrold Nadler—the warden denied Rosenberg’s petition, stating that the nature of her conviction made her too much of a flight risk. Appeal after appeal followed—all of them unsuccessful. Then something—to this day Rosenberg doesn’t know what—shifted and out of nowhere she got word that the visit was approved.

First, however, there were documents for Rosenberg to sign, swearing not to escape. She was later prepared for the journey: “The lieutenant cuffed me, but did not wrap me in chains... They put me in a car and drove me to a small airport where we boarded an eight-seat Learjet… We were met by a small army. There were more than fifty agents of every variety and rank: state police, Westchester County police, Danbury Bureau of Prison personnel, FBI agents, and U.S. marshals—all these people assembled to take me to the Danbury, Connecticut hospital.” After a short supervised visit, Rosenberg returned to her cell in Marianna Prison, grateful to have said goodbye to her beloved father but acutely aware of the class privilege that made the encounter possible.

Rosenberg rails at the racism, sexism, homophobia, and classism that define prison life and An American Radical is brimming with fury at the inequities she and other female prisoners were forced to endure. Whether focusing on AIDS or the disproportionate punishments meted out to political prisoners—Rosenberg, for example, was given fifty-eight years for weapons possession, an offense that typically carries a five-year sentence--her struggle to retain her humanity is both laudable and inspiring.

President Clinton granted Rosenberg executive clemency on his last day in office, January 20, 2001. While the book ends here—and says nothing about her activities during the subsequent ten years—Rosenberg turns a floodlight on the many political prisoners still languishing in U.S. jails. “The government does not recognize the existence of political prisoners in our country,” she writes. An American Radical shatters the denial that has allowed this to occur.