American Studies (Volume 48, Number 2): Homosexuals in Unexpected Places?

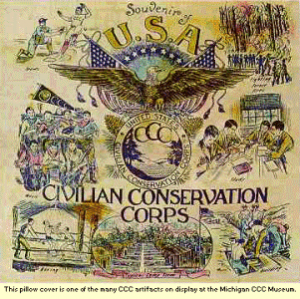

In this special issue of American Studies, the editors promise a review that will challenge the preconceived notions of “metronormativity” in the LGBT community. From Dartmouth in the 1920s, to the work camps of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), to the eroticization of the rural male in the work of a visual artist, to Small Town USA, the gays are everywhere. What is surprising about this is that we’re supposed to find this surprising.

In the introduction to this issue, Colin R. Johnson, Assistant Professor of Gender Studies at Indiana University, introduces us to the concept of metronormativity, the idea that queer spaces are somehow solely urban. Unfortunately, this concept is not one that has ever been taken seriously in queer studies. Surely, the young gay person finding freedom in the big city is a common story, but it has never been the only or predominant one amongst those well-versed in queer history. As we move from the introduction, each of the four essays claiming to explore “unexpected” homosexuality falls short.

The first two, set in 1920's Dartmouth and the work camps of the CCC, are perhaps just as stereotypical and just as expected as the “metronormativity” myth. Homosocial environments have known been long as places where queerness can flourish virtually undetected, especially since activities that would be considered queer in mixed-gender environments (like men portraying women in the theatre) lose that connotation in homosocial ones. Unfortunately, this means that the line between true queerness and situational homosexuality and pseudo-queer activities become coded as queer by the outside observer, a mistake made all too frequently in these two essays.

In the third, “Southern Backwardness,” the reader is expected, one presumes, to be shocked by the eroticization of the rural, a ho-hum standard ploy in gay male erotica. The muscle-bound rube, the working class male, the hard-living blue collar hero, all have been the subject of gay male (and straight female) fantasy for a very long time. What, I ask, is new, interesting or exciting about that?

Finally, in the fourth essay, we get to the only particularly new or interesting view of queer youth culture, the claiming and queering of spaces inextricably connected to white bread, suburban Americana: donut shops, Wal-Mart, book stores and public libraries. The emergence of a queer youth culture is new, a product of the decades-long struggle to eliminate the closet as a force in the lives of young gay people. However, the locations chosen are not particularly surprising to those of us intimately familiar with the youth culture (queer or otherwise) of the suburbs. Ensconced in the middle of white bread America, there isn’t much of a choice for suburban youth but to claim places such as these as free youth spaces.

Ultimately, the most expected (though no less disappointing) aspect of this “unexpected” look at non-metro homosexuals is that the lesbian is invisible. Considering the lesbian love of claiming non-metropolitan locales and the particularly suburban and rural bent to much of lesbian culture, the absence of the Sapphic is particularly inappropriate here.

My recommendation? Skip it. At this late stage, there are a plethora of queer studies journals that do a far better job of illuminating the lives and histories of LGBT Americans.