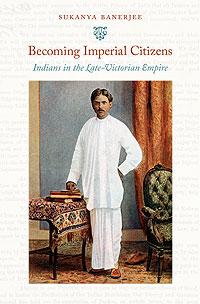

Becoming Imperial Citizens: Indians in the Late-Victorian Empire

It’s important to state here that Becoming Imperial Citizens is a work of research best suited for academic audiences. The upper-level vocabulary, combined with analysis, makes for quite a heavy reading.

Sukanya Banerjee’s work looks at the British Empire and citizenship with reference to Indians during, as the title notes, the late Victorian period. From documents covering Mahatma Ghandi’s early years in South Africa to Cornelia Sorabji (Oxford’s first female law student), Banerjee examines the complexities of Indian citizenship under imperial control.

The text provides many examples of how difficult it was for Indian citizens to actually be treated as such. The British system, while quite ideal on paper, did not treat its Indian subjects as citizens. Nevertheless, India proved to be more progressive than England itself when it came to achieving franchise. A good example is Dadabhai Naoroji, who utilized colonial language to appease Britain while advocating for India’s needs. For the good of England, he argued, her Indian subjects required the same rights and justice as her English-born.

To complicate matters, even when individuals like Surendranath Banerjea (one of the first Indians with the Indian Civil Service) complied with empirical expectations, they did not become citizens. Indians had to travel all the way to London, England to take the ICS exam, which greatly reduced Indian chances of admission—many Indians simply couldn’t afford the trip. When Banerjea made it into the ICS, a supposedly permanent position, he was overworked at first, and then expelled. He attempted to go to plan B, law, but his history with ICS ruined his chances. Ghandi, in his writings, also noted discrimination against Indians in South Africa, which was evident as soon as he arrived there.

Banerjee does not merely examine British-educated Indians; she presents their writings and documents to show that the Indian caste system was another obstacle to gaining real citizenship within the empire. Professional occupations in India were a privilege, for the elite. The exam for ICS, for example, was opened to those who did not have a university education but ‘crammer’ preparation. To keep up the lower class individuals who passed the ICS exam, candidates had to show mastery of such elite skills as horsemanship and ‘gentlemanly’ manners. In gaining a foothold for Indian traders in South Africa, Ghandi himself initially downplayed unskilled labourers, conforming to the stereotypes of the day.

While fighting for the right of real citizenship, the affluent people presented in Banerjee’s analysis were well aware of the intricate factors involved in imperial politics. They knew how to play the imperial game in order to make small, gradual gains towards the goal of realized citizenship for all Indian subjects.

Becoming Imperial Citizens is a great resource for anybody studying the British Colonial Regime’s legal, social, or political history. The struggle for equal status in daily living is not specific to India, but experienced by all former British colonies. When taking action against the government, it took inspirational actions to gradually tear down racial, class, and gender obstacles to citizenship for all.