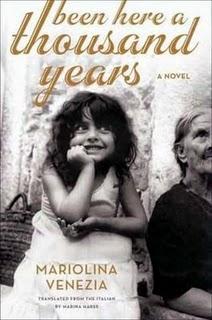

Been Here a Thousand Years

Been Here a Thousand Years, Mariolina Venezia’s novel that sweeps across Italy’s history from 1861 to 1989, with certain ideas and images already floating in the periphery: Berlusconi’s wife explaining the reasons for their divorce, my own memories of whistles and blatant gazes from men during a visit to Florence, high fashion seemingly making women into glorified clothes hangers. To tell the tale of a family of women over a historical timeline from Italy’s unification through fascism seemed a daunting and exhausting task. Venezia tells a multifarious story that, for the most part, glides above what could otherwise be a tiresome history lesson, burdened with sexism.

I have always enjoyed historical fiction. The combination of a creative story set against a factual backdrop intrigues and excites me. Venezia does an amazing job of writing an almost magical story of five generations of women in the Falcone family with the very real story of Italy’s past. Themes of womanly and motherly love that border on mythical contrast with the destruction of World War I and II. National power struggles, dictatorships, and monarchies parallel sisters’ rivalries, marriage proposals, births, and the lifelong search for fulfillment. Venezia does not attempt to justify or condemn the lives the women choose or are forced into. Instead, she creates a beautiful and expansive story in which sexism is simply a given, a historical fact.

At times, it feels like the author is taking on too much. The reader is forced to keep tabs on an endless cast of characters who, although each is well-crafted and interesting, pop in and out of the novel with such frequency that references to the family tree on the third page are more necessary than I would like. Venezia is creative with her use of narration and her manipulation of time and dialogue, but in the muddle of too many voices, it doesn’t feel as if she truly hits her stride until the last fifty pages. Gioia, the last of the Falcone women to take the helm of their history, is by far the most interesting and multifaceted. To some extent, it seems as if each character before her was a writing exercise the author used to develop her final masterpiece.

Writing this review is not easy, and I feel as if I need to write a thirty page essay on this novel to truly find my conclusions about it. I am reminded of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude—a multitude of characters, a rich history, poetic language (translator Marina Harss does a stunning job), complex motifs, and countless interacting story lines that each can be dissected, analyzed, and most importantly, enjoyed. This book is best for readers who can commit to more than light fiction, and best if one can block out preconceived ideas and images of Italy—something I could not do. Mariolina Venezia’s work is rich enough on its own.