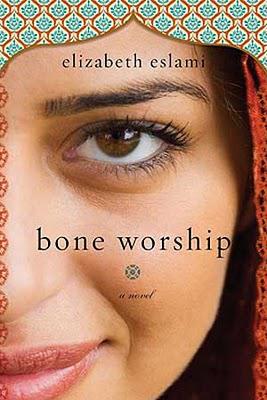

Bone Worship

After finishing Bone Worship, I wanted to let it sit for a while before I reacted. Full disclosure: Elizabeth Eslami is a friend, and has blessed a book of mine with a glowing review. Situations like this can be awkward, so over the years I’ve developed a de facto policy when I find myself faced with reviewing a work by a friend. Generally speaking, if I find a friend’s book lacking in more respects than is acceptable, I tend not to review it. Fortunately that’s not the case here; Eslami’s debut novel is wonderful.

Jasmine Fahroodhi is a young woman with possibly the worst case of sophomore slump on record, which endures until her parents pick her up at graduation—only a few days after she lets them know she’d flunked out of school. Her father, a Persian-born doctor, seems less rattled by his daughter’s failure in school than by her choice of a major other than pre-med. Jasmine goes home to Georgia with her parents, where her father embarks on his “Plan B” for Jasmine’s future: hastegar, an arranged marriage. Jasmine, as unenthusiastic about home life as she had been at the University of Chicago, musters only the mildest American feminist opposition to this plan.

Dr. Fahroodhi is a classic fish out of water. Opaque even to his family, he is frequently hostile to Jasmine—“you’re stupid” being among his most frequent utterances. Her reluctantly co-dependent mother, born in the Old South, oddly supports her husband’s plans for an arranged marriage, helping him take out “Bride Available” ads in newspapers catering to Iranian-Americans. Jasmine reluctantly goes along with the plan, which—true to the book’s dust-cover teaser—results in humorous and awkward meetings with potential suitors, and then the unexpected happens, though not in the saccharine way this telegraphic summary might lead you to expect. In the meantime, Jasmine stumbles through a series of suburban job-hunting moments, culminating in one of those menial jobs a lucky person finds every now and then that utterly transforms them.

That’s the plot, but this novel isn’t really as much about plot as it is character, primarily that of Jasmine’s father. Jasmine’s relationship with her difficult father is the central point of the novel. Early on, she remarks that despite having known him all her life, “If I had to stand up at his funeral one day and tell the world about his desires and hopes and who he was as a person, I’d stand there mute.” In the novel’s first pages Jasmine lists the seven big things she knows about her father—his lifelong aversion to broccoli; his habit of calling his parents in Iran every other Sunday; the fact that he used to beat their dogs with a shovel; his having pushed a young cousin off a wall in Iran, badly injuring her, and a few others as well distributed along the spectrum from banal to vile. As the chapters unfold, Jasmine examines each of those seven known things in some detail. Eslami deftly structures the narrative around each of these channel markers.

Eslami’s portrayal of Dr. Fahroodhi is frank, and there is much to dislike in the man. His vulnerabilities, explored as the book unfolds, may make the reader cringe on his behalf, but they do little to soften our impression of him; they mainly help reveal what broke him. Jasmine’s relationship with her father is one of those that might seem inexplicable to an outsider, a bond that apparently persists out of duty alone, with neither party gaining much. At that, it’s like a lot of father-daughter relationships. There is tenderness there, but it’s deeply masked: the unrequited love of a daughter for a man who observed his children “from a safe distance like a potentially flammable lab experiment,” the arguable love of a man for his incomprehensibly un-Persian daughter that mainly manifests as frustration and anger. That anger and frustration, felt on both sides, never comes to a head. Maybe it’s American of me, but I found myself wishing for a more open confrontation between the two.

All that notwithstanding, Eslami has not created a loveless father. Jasmine sees his love for her mother plainly and from a bit of a remove, as though it’s a specimen described in one of the natural history volumes she checks out of the small local library. One of the things I liked best in Bone Worship is Eslami's use of images, memories, passing conversations, and other bits of detail to represent Jasmine’s exploration of her relationship with her family and herself. The whole hastegar plot itself is a fair symbol for the involuntary relationship Jasmine has with her family—as we each have with our families. Eslami weaves these images into her prose quite deftly, and in ways that made me frankly envious of her sight. This is a hell of a fine novel, especially for a debut.

Cross-posted at Coyote Crossing