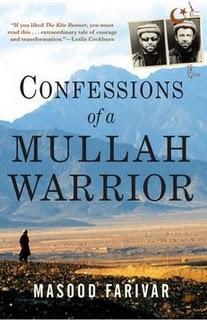

Confessions of a Mullah Warrior

“History is full of great men,” Masood Farivar declares as a young man, about a third of the way into his memoir, Confessions of a Mullah Warrior. Luckily, Uncle Jaan Agha rhetorically slaps him on the back of the head, half a page later. The topic is dropped then, and for the remainder of the narrative. Confessions of a Mullah Warrior is full of Farivar’s mostly unintentional awkwardness with women, which is at times induced by modesty, at times total miscommunication, and mostly, it is innocent.

Farivar tells the story of his maturation, even though he seems to continually avoid growing up. Focusing on incidentals and plot rather than personal details, the book leaves the reader with a greater sense of Afghan customs and heritage than of the man who is Masood Farivar.

Farivar surveys his past longingly, abashedly, and ashamedly. Longing for the sense of homeland lost, he emigrates from Afghanistan to Pakistan and finally to the U.S., seemingly moving farther in body and spirit from a sense of belonging. All the while, Farivar seems to yearn more to fit into his environment than to be himself, and he seems a bashful adolescent well past the age. Farivar shamefully reproaches himself for trying to fit—and then for fitting in too well.

Farivar’s concerted attempt at placing himself in the center of world events and of using his life as a metaphor for every other mujahideen, martyr, and bystander causes him to be lost in the narrative. This is especially true as Farivar allows himself to indulge in some of the more irritating themes of the genre. There is also a constant need to find humor in a naive attempt to reclaim ownership of one’s past, and the memoir is replete with retrospective irony, which is pointed out to the reader each and every time.

Overall, while Confessions of a Mullah Warrior gives the reader a greater sense of the Afghani experience of repetitive conflicts and exile, it does not give the reader a sense of Masood Farivar.