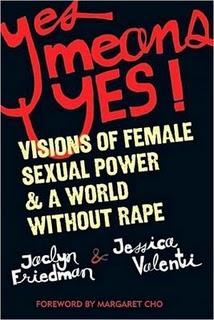

Yes Means Yes!: Visions of Female Sexual Power and A World Without Rape

The Apostate: My initial reaction when I heard about the Yes Means Yes! anthology was mixed. It seemed that the problem of rape was being used for a catchy slogan's sake (the catchy slogan being a play on the anti-rape "no means no" rule), and not because it made any real sense. I wasn't sure where you could go with that—connecting sexuality with rape culture in a way that was meaningful for actual cultural change and impact on women's lives.

Professor What If: The introduction notes that the book intends to offer “a frank and in-depth conversation about forward-thinking ways to battle-rape culture,” and the book truly does contain many frank, in-depth conversations that formulate ways to rethink not only preventing rape, but also re-shaping the way we approach sex and sexuality. While the reasons behind the book are laudable, I find the claim that valuing female sexual pleasure will stop rape the book puts forward a bit too simplistic. Although the book nods to the complex socio-cultural factors that perpetuate rape culture, it stops short of really grappling with how rape is a by-product of our patriarchal, militarized, commodified world. I do think this is a very important book that makes crucial contributions to re-thinking sexuality, but it is only part of a much needed conversation we need to have—both in books and in blogs—about eradicating rape culture.

The Apostate: I think rape culture should have been expounded upon more. I don't think people understand the difference between rape and rape culture, and that wasn't really addressed, which gave rise to some of the confusion around why anyone thought Yes Means Yes! would stop rape—the writers didn't think it would! They just want to dismantle rape culture, which is a bigger and more amorphous thing than the specific crime of rape, even if rape takes place within the context of rape culture.

Professor What If: I was impressed with the broad coverage of the book and the diversity of voices. I especially appreciated those pieces that emphasized anti-rape activism must include teaching men not to rape and helping men to recognize rape. Jill Filipovic’s piece, for example, was very effective in examining the social-cultural contexts of rape culture and the need to include men in anti-rape activism and education. I also liked the inclusion of queer, male, fat, sex work, and BDSM perspectives.

The Apostate: My favorite essay was Thomas MacAuley Millar’s. It really dismantled the perceptions of sex as something that is done to you, as a woman, rather than something you (enthusiastically) participate in. That is not a concept enough people understand; and although I get it, I have never seen it articulated so well as Millar did. His essay was beautifully written, cogent, with a great metaphor about sex as music. The commodity model of sex is one of the biggest hurdles women face, if they act like they are free to pursue their pleasure. People don't think their pleasure is really part of the picture at all, since women are the object, not the subject. And another thing: I had never realized how "no means no" continues to frame the sex as between a predator and prey, as Julia Serano defined the terms.

Professor What If: Many of the authors argued against the 'power over' dynamic that shapes our thinking about sexuality by emphasizing mutual consent, doing away with the competition model of sex, ensuring certain partners (namely women) are not objectified/dehumanized, etc. I think this re-thinking of the power dynamics in relation to sex/sexuality are crucial. However, they must also be addressed in relation to those politics of domination that shape our society—patriarchy, capitalism, sexism, racism. Also, I wonder about the subtitle “visions of female sexual power.” Do we really want to rethink sexuality in terms of power? Doesn’t this go against the mutual consent/pleasure model the book upholds?

The Apostate: The emphasis on sexual assault—and personal stories of pain and damage around that—got overwhelming in the second half of the book. The joy of enthusiastically consenting sex got lost in there. I think that focusing on how rape and sexual assault affect women's lives is very important, especially as so much of this reality is not captured in statistics or on the news, but perhaps sex as pain should not have predominated quite as much.

Professor What If: I think an analysis of rape in same-sex or non-heterosexual relationships is missing. In keeping with this notion, the book frames women as rape victims, not covering boys and men as also victims/survivors of rape. For example, as rape within systems like the Catholic Church and public schools is prevalent, this seems a key omission. How could the rape culture condoned by religious establishments or the military be addressed via the “yes means yes” paradigm? In ways, the book leaves out the institutionalized aspect of rape and focuses on “individual rape scripts.” In so doing, it doesn’t fully examine those social structures and institutions that shape sexuality and perpetuate rape culture—the family, the church, the law, the military, etc.

The Apostate: The overall feel I got from the book was very "alternative." It was very citified, and very margins-of-society, written by people we don't hear from on a daily basis in mainstream coverage. Those voices are all the more crucial for being so marginalized, and also because it is on the margins of society that the worst abuses happen. That said, I think it lacked a certain degree of balance. I did think it covered a wide range of issues and perspectives—except for married, heterosexual, middle class sexuality and the sexuality of older people. The only reason I would have liked to see that balance is to "normalize" these issues for the mainstream; so much of this sort of thing is hidden, under wraps, and allowing only the margins to speak out about it gives the deceptive impression that the problem of rape culture is not the problem of all women—which it most certainly is.

Professor What If: I love blogs and blogging, but books are not blogs. Rather than trying to make the two mediums the same, I think we should value each medium (print v. online) in its own right. I found the “hyper-link” structure did not translate well into print format. Further, in keeping with the “blog format” of the book, many of the pieces were written in the less formal, talky style of blogs. Javacia Harris, for example, writes “Don’t get me wrong. I’m certainly not anti-sexy—I’ve been to my fair share of striptease aerobics classes.” This style seems too light for the aims outlined in the introduction and this style allows comments like these to be tossed out with no analysis of the wider cultural contexts that defines normative notions of “sexy” and results in the very existence of striptease aerobics classes in the first place.

Too often the attitude that framed the arguments in the book is that any choice is ok as long as you know why you’re making it. This “sexual empowering choices model” is too simplistic. This is partly due to choosing a “blog style” for the book—a style that makes the book seem a bit too light given the subject matter at hand. While blogs work in a conversational, of-the-minute style, books allow for more thoughtful, hard-hitting, heavily researched writing. Both have their merits, but trying to write a book that functions like a blog makes me wonder about the purpose of going the print publication route; if one is not going to take advantage of a book format (and go into deeper analysis/research), stick to a blog (and indeed, the editors have a blog of the same name now up and running.

The Apostate: I also thought the hyperlink theme was a little redundant. I liked the idea to begin with, but I ended up skipping the lists at the end of each essay and just read linearly. I did glance at a few and thought they didn't always make sense; they tended to include a quarter of the book each time, after every essay. A thematic unity among pieces kind of fell into one's head automatically, so I didn't see the necessity of that. As for the authors being mostly bloggers and part of the blogging community, I do think that it was perhaps a little insular and self-referential. For someone outside that community of bloggers, perhaps a lot of this stuff would be very new—some context is missing and some pieces are more bewildering than others. But overall, the hyperlinking style is easily ignored and doesn't detract, even if it doesn't add.

Professor What If: Examining the many factors that contribute to rape culture is helpful in addressing the pervasiveness of sexual violence. However, I still found there was a bit too much emphasis on what females do/do not do. The introduction notes that often what is missing in analyses of rape is the rapist. This book, with its focus on "yes” and on female’s “owning” their sexuality also under-analyzes rapists, instead focusing on women’s need to familiarize themselves with “enthusiastic consent.” In a strange way, the book thus keeps the onus of changing rape culture squarely on women’s shoulders. Many of the solutions seem a bit too individualized—as if becoming sexually empowered and educated will be enough to stop rape (or at least stop it from happening to oneself). While many of the texts offer useful, concrete suggestions to move towards a world without rape, I think more analysis of how the politics of domination upheld within patriarchy, capitalism, and militarism (all which profoundly shape our world) was needed. Also, we need to examine how intertwined violence and sexuality are in contemporary society—violence is so pervasive that it cannot be extracted from sex/sexuality. All of the enthusiastic “yes’s” in the world won’t change this.

The Apostate: A lot of issues being talked about are really not discussed in our society and they need to be. And I was totally won over by the thesis of the book—that a woman's right and enthusiastic consent to sex were central to how sex and sexual violence are perceived. I’m really glad to see a somewhat mainstream book about women's experiences and hopes for a positive, enthusiastic, feminist ideal that also includes women as sexual creatures: horny, lusty, and slutty. Jaclyn Friedman's essay about overt sexuality really spoke to me on that front.

Professor What If: The book is a really good first step towards re-thinking rape culture. Like Valenti’s other books, it will speak to many young feminists. However, being the theory-loving academic that I am, I found myself writing in the margins comments such as, “But where is the theory?” For that reason, I really liked Lee Jacobs Riggs account of our “sex negative” culture and the ways she also addressed the prisons/the criminal legal system and other oppressive systems. I would have liked more hard-hitting pieces like the ones by Coco Fusco and Miriam Zoila Perez (which were my favorites). Too often elsewhere, I came across the word “probably” being used to assess information. In the end, I also found the attack on second-wavers off-putting. Why does this have to be one of the defining characteristics of third wave texts? We need to get over the feminist blame game. No one “wave” has all the answers, and I think sometimes third wave feminism fails to address it’s own shortcomings.

A necessary critique of the decision to post a review of YMY can be found at http://guyaneseterror.blogspot.com/2009/02/response.html