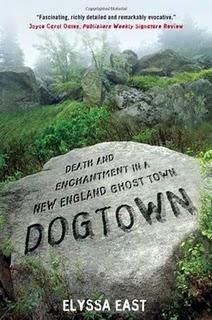

Dogtown: Death and Enchantment in a New England Ghost Town

"Anybody that’s ever lived on earth knows that the earth is the geography of our being." - Charles Olson

Dogtown is a rocky 3,000-acre swath occupying the interior centre of Cape Ann Peninsula in the northeast corner of Massachusetts. Gloucester, renowned as a fishing village, is located on Cape Ann (the fishermen of The Perfect Storm worked out of Gloucester). British colonists cut down trees and built homes on the peninsula in an area known as the Commons Settlement. Logging subsequently became important to the colony’s survival. Additional clearing by herds of voracious cattle denuded the cape, but by the late eighteenth century the population had abandoned the Commons and moved to the coastal reaches. Trees and bushes returned. The interior of Cape Ann has been a wilderness ever since—not wilderness comparable to northern Canada or the Grand Tetons, but wild enough for a place only twenty-five miles from Boston. This tract, including the Commons, came to be called Dogtown; in part due to packs of dogs that ran free there, in part because it attracted squatters on the downside of the socioeconomic scale.

Elyssa East, author of this intelligent book, discovered Dogtown in the 1990s when she was studying art history. A last-ditch attempt to complete an assignment led her to Marsden Hartley, the important—if little known—American Modernist painter. Hartley, who was gay, lonely, and suicidal, stumbled onto Dogtown, painted his best landscapes there, and consequently experienced a spiritual renaissance. East, too, was feeling a loss of the “hopeful sense of discovery and wonder.” She went to Dogtown to see if she could find her own renewal. Dogtown is the result of her ten-year search.

What she discovered was a region with an extraordinary, schizophrenic spirit of place. Just as Hartley had painted there, the renowned postmodern poet Charles Olson had employed Dogtown creatively in his signature work, The Maximus Poems. Other artists, and many a regular citizen, found there a life-affirming inspiration. Others thought it a wasteland, a haunted, foreboding place to be avoided. Some found madness and tragedy.

In 1984, Anne Natti, a teacher, had been brutally murdered in Dogtown. She was walking her dog when attacked from behind, her skull fractured by a forty-pound rock. The assailant stripped her, but did not rape her. He hid her still-alive body in a copse, stuffing her face into the muddy ground. She died slowly and horribly. The murderer was a Gloucester boy with a previous conviction for exposing himself. Cape Anners took him to be strange, but never a potential killer.

Dogtown has many good portraits of locals, people whom East interviewed. It is interestingly structured, alternating chapters from the remote past with an account of Anne Natti’s murder, the investigation, and the trial, all of it interwoven with East’s explorations of Dogtown’s geography and her inner quest. This varied content makes for a rich book, although the murder at its centre, even flatly and forensically narrated, makes for harrowing reading.

East has her facts mostly in order, and she is enlightening on certain aspects of colonial history, deploying her woman’s awareness for a different look at the Revolutionary War—so storied in American myth, yet which left behind many sorrowful, unsung widows forced to fend for themselves. In a work so replete in fact, errors are nearly inevitable: East calls Robert Duncan a novelist, but he was a poet, and although William Carlos Williams, arguably the greatest twentieth-century American poet, was invited to teach at Black Mountain College, he never did. The book could also use more maps; the lone one in the book is not nearly adequate for the text. A photo section would have been a worthy addition, too. These are small-time caveats. In all, East has produced a fine book—her debut—and of noteworthy consequence.