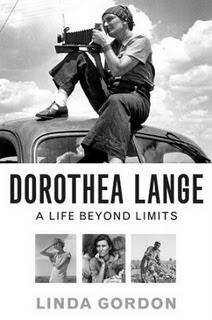

Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits

Ask people to picture the Great Depression of the 1930s, and they’ll likely envision bread lines, rural poverty, and ragged families trying to hold destitution at bay. One photo, of a tired-looking woman, personifies the crisis. Called Migrant Mother, it depicts a worried female, hand on chin, looking into the distance as two cowering toddlers curl into her body.

Taken by Dorothea Lange, the chillingly beautiful, if austere, photo has been used for nearly eighty years to illustrate the personal toll of economic troubles. But while this image has become iconic, the artist who made Migrant Mother recognizable has been largely forgotten.

Social historian Linda Gordon seeks to fix this and her fascinating biography of Lange introduces a complex, driven, and multi-talented woman. Gordon starts the book in late-1890’s Hoboken, New Jersey, Lange’s hometown, and reports that she had a childhood of dramatic ups-and-downs: A bout of polio in 1902, when she was seven, left her with a deformed foot and her parents’ divorce when she as 12 triggered lifelong abandonment issues. Still, proximity to Manhattan satisfied Lange’s itch for adventure, and she repeatedly ditched school to explore the City’s ethnic enclaves. By the time she migrated west, landing in San Francisco in 1918, she was hungry for something new and was immediately drawn into bohemian circles that included artists Anne Brightman, Imogen Cunningham, and Consuelo Kanaga. In short order, Lange discovered her niche, establishing herself as a professional photographer. Her work initially involved portraiture and she set up shop taking pictures of the well heeled.

Along the way she met Maynard Dixon, an outdoorsman and painter twenty years her senior. Their tumultuous—if always respectful—relationship included a marriage and two sons and lasted until Lange got involved with sociologist Paul Schuster Taylor in the mid-1930s.

Taylor was the love of Lange’s life, a collaborator and partner. The two tromped around the U.S. as employees of the Farm Security Administration, she with a camera, he with a notepad, and together documented conditions in rural states. They were among the first to draw attention to mass migration from the South, publicizing the trek of “Okies” fleeing the Dust Bowl for the greener pastures of the West. Gordon points out the unintended consequence of this coverage—their focus on desperate whites unwittingly diverted attention from people of color living in even worse penury.

Gordon also zeroes in on another less than rosy aspect of the Lange-Taylor dyad—the virtual abandonment of their six children in order to work. Gordon captures the dynamic of the newly-blended family succinctly: “Today’s child development wisdom, considers the moment of divorce as the worst possible moment to send children away from their parents. When children fear loss of parents, they need reassurance that their parents won’t desert them and that the break-up is not their fault. The four parents involved in this story did not share today’s psychological understanding of children’s needs. Rather, they assumed, as most early twentieth-century experts did, that children were resilient and adaptable so long as their physical care was good.”

That said, Gordon reports that Lange was pained by the separation and often suffered from stress-induced health problems. At the same time she refused to return home and instead produced scores of enduring images to illuminate women’s oppression, racism, and workplace exploitation. Gordon calls her “America’s preeminent photographer of democracy” and credits her for showcasing what needed to be changed for democracy to flourish. Clearly ahead of her times, Lange defied expectations about women’s place and remains a relevant—and inspiring—role model.