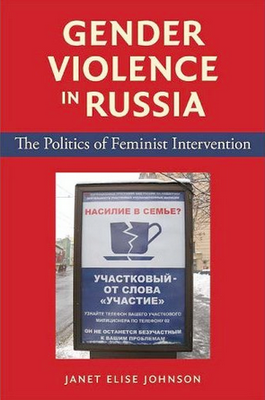

Gender Violence in Russia: The Politics of Feminist Intervention

In periods of rapid social change, the poets of one ideological system or another rush to find the cogent metaphor or, more recently, the winning soundbite, that will interpret the change to suit their own ends, to control meaning. To find and sell the right descriptive phrase is to raise the flag of possession over a historical event. For example, the collapse of the Soviet Union—or, even more stridently, the U.S. victory in the Cold War—spins the end of the 1980s, the end of history, as some proclaimed it, as a triumph of righteousness, rendered even more morally spectacular by the supposed “coldness” of the conflict, and the ushering in of a new world order. That’s why a book like Janet Johnson’s Gender Violence in Russia is so badly needed.

The book lacks the poetry of impassioned argument, and it is heavy with charts and appendices and social science-y apparatus, but it makes a couple of very painful and crucial observations. One is that the end of the “evil empire” actually made social conditions for Russian women considerably worse. The incidence of violence against women demonstrably worsened as official attitudes, in spite of increasing international pressure, actually resulted in changing criminal codes to the detriment of women’s rights. Trafficking in women, rape, sexual harassment, domestic violence all got worse in the 1990s, and the Russian government relied on age-old sexist lies to justify their apathy.

A different sort of ideological poetry, one also confronted painfully in this book, is the emergence of global feminism in the 1990s. The movement is inscribed in the U.N. Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women (1993) and in the Beijing Declaration on Women (1995) and in a new level of worldwide feminist activism aiming to confront injustice and make the world see that women’s rights are human rights. As if the pronouncement the other day by a Saudi judge justifying “slapping a spendthrift wife” weren’t warning enough, the very mixed picture of the women’s rights movement in Russia should warn us against triumphant rhetoric concerning the record of global feminist intervention. Clearly there has been a powerful “push-back,” not only from the old guardians of patriarchy but from those identifying global human rights movements as forms of neocolonialist western interference that must be resisted.

The conclusion Johnson’s study reaches is a rather dreary one: that what really works, in terms of feminist intervention, are “alliances between global feminists and large donors.” Money talks, apparently; or rather its use in creating organizations for women’s advocacy is the best agent for social change. What Johnson calls “flexible and responsive funding” is the key, targeting funds where they are most needed and can do the most good to protect women and to begin to change cultures of violence which have proven fearfully resistant to change.

I agree with some of the above comment but am not sure why Muslim nations are mentioned? Islam is not inherently oppressive, nor are nations that predominantly Muslim necessarily run as religious states. It seems unfair to point to one religious group, nation, or cultural tradition as so much worse than others. Even in the Western world (which can arguably include Russia, depending on who you ask), women don't exactly have equal standing. It doesn't help level the playing field to make biased comments against religious groups.

I agree--most countries need foreign financial aid, whether these countries are largely poor or because their populations are sexist and do not support the funding of women's shelters and the like.

I read that there is something like ONE women's shelter in Moscow and there are very few beds. And that because women don't have where to go and rent has skyrocketed, many abused women must keep living with their abusers even after divorce!

Apparently they have a saying in Russia: "if a man hits you, he loves you." You know, because Russians are so passionate that they express everything, uh, intensely? What a fabulous excuse!

And let's not even get into Muslim nations' policies and customs...

Sounds like a very interesting, if depressing, book. Living in privileged Western nations it is ridiculously easy to forget how so very easy we have it compared to women elsewhere in the world. It is important to stay informed, sign petitions, donate $, spread the word, do whatever we can.

Injustice against one person affects everyone, in one way or another.