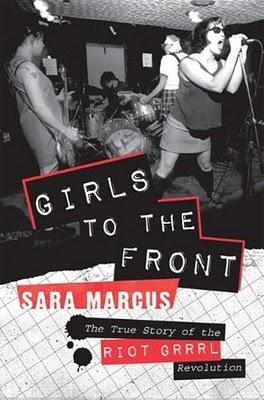

Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution

First, an admission: like several feminist friends in my age group, riot grrrl didn’t make a profound impact of me until college. I was ten in 1993, the year Sara Marcus claims as pivotal for the movement in her book Girls to the Front. I was moving away from Mariah Carey and getting into the Pet Shop Boys. Riot grrrl was first on my radar through mainstream distortion in the pages of Spin and in the Spice Girls’ defanged “girl power” message. Marcus’s book is a great reintroduction and a valuable entry point for folks who have only a cursory knowledge of riot grrrl.

I especially appreciate that, despite the book’s monolithic title, Marcus incorporates the shared experiences of many girl participants. Riot grrrl tends to be defined by its adult-aged bands, with Bikini Kill and Bratmobile representing the movement. But many teenage girls were inspired by these bands. Some formed ‘zines and bands of their own, like Girl Friend founder Christina Woolner and Heavens to Betsy’s Tracy Sawyer and Corin Tucker. Not all of their contributions were preserved or recorded, so the book’s intervention is all the more important.

Some of these girls also came from working class or single-parent households or did not attend college. Furthermore, while much is made of the movement’s Pacific Northwest origins and identification with liberal arts colleges like Evergreen, Marcus is quick to refute essentializing class assumptions. Riot grrrl’s class heterogeneity becomes more pronounced when Bikini Kill and Bratmobile relocate in Washington D.C. and contend with the hardcore scene, which was primarily peopled by diplomats’ children.

Marcus challenges the notion that riot grrrl was sustained exclusively by white, middle-class, college-educated women. She also points out the movement’s aspirations toward queer inclusiveness were complicated by the efforts of predominantly straight or bi-curious cisgender females. Previous interpretations of riot grrrl represent it as a celebration of white girls challenging gender politics in a vacuum. Marcus points out how some girls created ‘zines, formed organizations, chaired panels, and created conferences challenging feminism’s inherent white privilege, racism, heteronormativity, and class politics, often causing contention and defensiveness from within.

Thus, I also liked reading that riot grrrl was an imperfect, discursive movement comprised of many conflicting opinions, belief systems, and identities. Despite third wave feminism’s investment in the fragmented female self, so often riot grrrl is depicted as a halcyon period for a then-nascent third wave. While it’s sad to read about in-fighting and rivalries, it’s refreshing to read differing opinions on philosophies and movement imperatives. As someone who’s participated in collective and politically-minded non-profit organizations, it seems a more honest representation.

Furthermore, the presence of male oppression from within informs riot grrrl in interesting ways. Riot grrrl formed in response to the right wing’s attack on feminism’s political gains as well as the cultural silencing of incest, sexual abuse, intimate partner violence, poor body image, and low self-esteem. It also opposed punk and hardcore’s exclusionary, homophobic, and misogynistic tendencies, best symbolized by the mosh pit, and implemented “girls in front” or “girls only” policies at shows. So it was really interesting to read about how bands like Fugazi aligned with riot grrrl, but were less willing to cede control over their audience.

In 1992, Fugazi and Bikini Kill played a Supreme Court protest. Frontman Ian MacKaye bristled at the idea of sharing the bill out of concern that the event would be misunderstood as a concert. He was also unable to reign in the aggressive inclinations of his predominantly white male fan base, and blamed the women in the audience who defended their space in the pit.

Marcus does something valuable with Girls to the Front. In representing riot grrrl’s imperfections and contradictions, as well as its relevance, she argues at once for its historical significance while challenging how we understand it. Make sure to check it out. Maybe it’ll convince you form a band with your best girlfriend and kick off a new revolution.

Cross posted from Feminist Music Geek

Excellent review. I really enjoyed reading it, and look forward to reading the book itself very soon. Am also glad to see there's a link posted to your blog; I can't wait to read it.

Fellow feminist music geek, Brianna