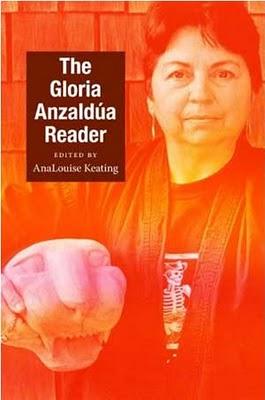

The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader

I should probably start by saying that I absolutely love Gloria Anzaldúa. She was a writer whose work focused mostly on her identities as a woman, Chicana, lesbian, feminist, etc.—identities she insisted could not be separated from one another. She is probably best known for co-editing This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color and for her book Borderlands/La Frontera, The New Mestiza.

Anzaldúa’s work engages me in a unique way, so I was equal parts ecstatic and apprehensive to start The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader. There are so many ways this could go—there could be too much new or obscure material, too much old material, too much academia, etc. Luckily for me, the book provides just the right balance and showcases Anzaldúa in a way that made me love her even more.

The book is divided into four sections: early writings, middle writings, images, and later writings. The divisions are based mostly on chronology, but there are also certain themes that are more prevalent in one section than another. Every section starts with a quote from Anzaldúa’s works and each piece has a short introduction. The introductions were very useful because they often provided the context of where it fit into Anzaldúa’s writing, listed some of the themes in the piece, and sometimes suggested what other works to read in order to explore the themes in that piece.

What I liked most about this book is that the editor, AnaLouise Keating, does a great job of including a bit of everything in almost every way. There are poems, fictional stories, autobiographical pieces, drawings, transcripts of talks and email exchanges, and so forth. In terms of content, there are at least a couple of pieces for all of the issues important to Anzaldúa: feminism, culture, queer studies, and disability. For example, the book contains an interview about spirituality and sexuality, a piece about her preference for the term “dyke” instead of “lesbian,” several pieces about culture and identity, a poem about the process of writing, an email exchange about disability, and the list goes on. It gives a great introduction to people who have never before read Anzaldúa’s work, but even die-hard fans will like the book because it includes a good amount of unpublished material.

I enjoyed almost everything included in this book, but I did earmark a few that stood out to me. There were a few pieces about how Anzaldúa started writing and the methods she uses for writing that I liked a lot. Similarly, a piece on creativity was one of my favorites, in which she explores the rational mind, imagination, her sensitivity to the world around her, and how all of that comes together when doing something like writing. There was also a very funny story about a woman so saddened by her husband’s death that he comes back as a ghost, at which point she realizes just how sick of him she really was.

One thing that I might have changed is the placement of the images. It was great to include them and a couple of the drawings make my list of favorite pieces in the book, but I think putting them all together in between other chapters seemed awkward. For me, it was reminiscent of a biography with photos in the middle. Perhaps spreading them throughout the chapters might have been better and more in tune with Anzaldúa’s own style of switching through mediums within the same work. But I have to admit that this is probably just nitpicking to find flaws in an otherwise incredible book.