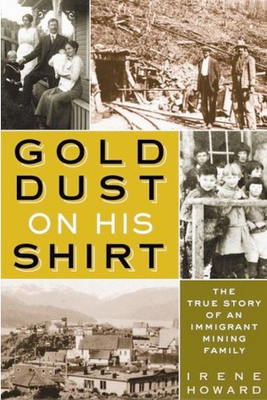

Gold Dust on His Shirt: The True Story of an Immigrant Mining Family

When you think about migrant memoirs of North America, stories of moving north from Latin America often come to mind more than those detailing moves east and west. Flipping around that common assumption, Gold Dust on His Shirt tells the story of Irene Howard’s Swedish-Norwegian immigrant family’s tumultuous life in Canada at the turn of the twentieth century.

After the death of her first husband in Norway, Howard’s mother Ingeborg immigrated to Canada. She left her young daughter Inga behind with the child’s grandparents, promising to send for Inga as soon as she was settled. Instead, once she arrived in Prince Rupert (in current day British Colombia), she met and married a Swede, Nils Alfred in 1913. Only seven years after Norway had gained its independence from Sweden, the couple felt—and was—thousands of miles from the political controversies of their homeland. Six months later, Ingeborg gave birth to their first son, Swedish-Norwegian-Canadian Arthur Ingemar. Over the years, Ingeborg and Alfred had several more children—Verner Erik, Nels Edwin, Irene—and were uprooted from their home several times. Alfred’s job working on the railroad demanded that the family relocate as work became available. As Alfred became involved with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and began mobilizing other immigrant workers, his job prospects were often limited due to his radical organizing.

Reading about language barriers, death by tuberculosis or mine collapse, police raids, and workers’ struggles against mining companies is a sobering experience. Living a reverse tale of sorts—an American in Denmark, mostly unable to speak Danish—I have a lot of empathy for the characters in this story. I also suspect that my own Norwegian background and my adopted Danish family made this a more interesting tale for me. I didn’t mind reading about characters named Sigurd Ullstreng, Olav Trygvasson, and Elling Erikssen Aarvig. For me, it was a bit comforting and homey—or “hygge,” as we say in Danish.

Howard’s history is fascinating, though her presentation is a bit dry. At times, the book reads like a genealogy scrapbook instead of a memoir, listing people and events in a factual if uninspiring way. For history buffs, this is no doubt enjoyable. I will admit to struggling at times to wade through the details of a time and place with which I have no real familiarity. Yet Howard’s story is valuable and often untold, and her objective storytelling—in which she often removes herself entirely from the narrative, even though she lived through the same events—is a refreshing departure from the self-centered account most memoirs provide. I suspect I will revisit this book for years to come, perhaps as my roots deepen and spread among the Nordic states and North America.

Howard was born in 1922 amidst her father’s career change from mining to fishing. That she has survived the last eighty-seven years—three less than my own still-living Norwegian grandmother—with her story intact, now fully documented and published, is no small feat. In Norwegian, we say, “gratulerer”—congratulations.

They also had another son named Roy Alfred (referred to as Freddie in mist of the book)!