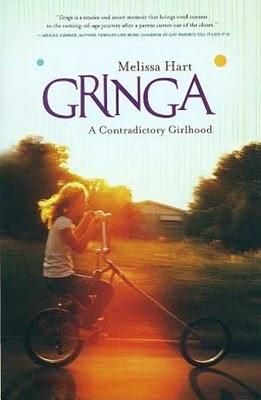

Gringa: A Contradictory Girlhood

When Melissa Hart was eight years old, her mother fell in love with Patricia, the woman who drove the school bus. Soon, Hart’s mother left her husband and moved in with Patricia, taking her children with her. Within months, however, Hart learned a heart-wrenching lesson when she discovered that the family courts of the 1970s didn’t regard a woman involved in a same-sex relationship as a fit mother. Hart's dad was given custody, and her mom was left to see her children every other weekend and a few weeks in the summer.

Living in the upscale Manhattan Beach with her upper class father and, after a short interlude, her new stepmother, the author longed for her too-seldom visits to her mother in Oxnard—a place not only geographically distant, but as culturally dissimilar as two places in Southern California could be. This split in her reality left the young Hart understandably confused about her own identity. In Oxnard, she was attracted to the culture of the predominantly Latino neighbors: their lively parties, delicious food, and the warmth that she perceived to be missing from her Manhattan Beach home. As she grew older, Hart longed to emulate her mother’s sexuality. But much to her chagrin, Hart discovered she was attracted to boys, and as much as she yearned to belong to the Latino culture, she was an outsider there as well.

While the writing is skilled and evocative, and the scenes are vivid, Hart gives us a book that doesn’t quite deliver a satisfying, cohesive story. Despite the themes that she revisits (one of the major themes of Gringa is the search for belonging by a girl whose mother was cruelly ostracized from her children by the legal system), her account lacks a defining arc. In some ways, this is not surprising. After all, this is a memoir, and real life is, by nature, episodic. What marks a skilled memoirist is her ability to sift through the events of her life and distill the story. Unless this is accomplished, her readers will ask themselves, “Why should I read this?”

While I was keenly interested in the problems Hart encounters as a result of her mother’s absence, her experiences as the daughter of a woman in a lesbian relationship, and the challenges she faced living with her often angry father and her new stepmother. I was far less interested in her account of getting a new car, her brief high school acting career, or her interlude as a student in Santa Barbara. A more judicious editor would likely have advised taking much of this material out because, while the writing is competent, it fails to overcome the problems in these chapters: a lack of narrative momentum, a clear relationship with the central story of the memoir, and a compelling conflict that makes the reader care.

Hart’s memoir is important in that it adds to our understanding of the impact of anti-gay prejudice and the bitter price children of lesbian and gay parents have been forced to pay; this is evoked with great emotional resonance in the book. Unfortunately, the strength of the memoir is diluted by the inclusion of material that seems extraneous.