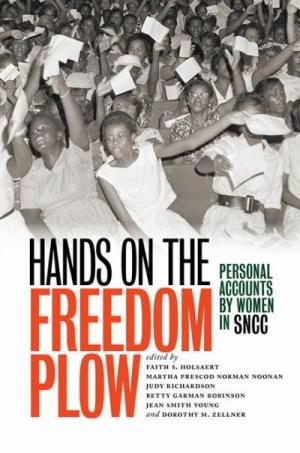

Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC

Much has been written about the courage and tenacity of the male ministers, activists, and young turks of the Civil Rights movement: Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., Julian Bond, Stokely Carmichael, and others. About the role of women, we know less.

Now, six women who were active in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) have rectified this omission by compiling their own testimonies and those of their colleagues in Hands on the Freedom Plow. Each of the fifty-two narratives acknowledges the centrality of women’s experience in the struggle for human rights in the southern United States in the late twentieth century. Weighing in at almost 600 pages, these compelling, at times harrowing personal stories recast the history of the Civil Rights movement from the perspective of women who lived it day by day.

Formed in 1960 by students—many of them from Black southern colleges—who had participated in lunch counter sit-ins, SNCC was in the forefront of desegregation and voter registration efforts. Theirs was a nearly impossible task, and the dangers they faced daily defy comprehension. Some of the accounts read more like dispatches from Srebrenica or Abu Ghraib than from southwest Georgia and Alabama. As the editors note in their introduction, “We took on the role of dismantling an ingrained system of social and political repression that was then almost a century old, and fought to replace it with a more just and egalitarian society.”

The pursuit of social justice meant the real possibility of mob violence, bodily injury, and the near-constant fear that those threats inspired. Women who chose this work often deferred their education and defied their families. Prathia Hall, the daughter of a Baptist minister from Philadelphia, was a recent college graduate when she joined the movement. She wrote plaintively about her commitment: “We had been warned in orientation sessions not to go into the field unless we were prepared to die.” Hall’s faith was tested in southwest Georgia, one of the most notorious and resistant sites of movement activity. Although she was shot and wounded by sniper fire, she continued her work in the movement. Her assailants were never identified or charged.

One of the book’s co-editors, Judy Richardson—currently a documentary film producer in Cambridge, Massachusetts—left Swarthmore College in the second half of freshman year in 1963 to go south to work for freedom in Cambridge, Maryland, then Atlanta, and later in Mississippi during Freedom Summer 1964. Richardson is a tiny, enthusiastic, and determined woman, who, when asked what she most valued about her movement experience, cited “working as a team and consensus decision making,” valuable lessons she continues to use in her work. Only recently has Richardson understood the emotional cost of her activism for her mother, who never acknowledged her own fear or being afraid for her daughter. She did not she ask her to come home—something Richardson considers a gift, a tremendous act of restraint on her mother’s part.

Another Hands on the Freedom Plow co-editor, Dorothy M. (Dottie) Zellner, joined the movement in 1960 after finishing at Queens College. A self-described daughter of Leftists who at seventeen read The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich for pleasure, Zellner was inspired by the activism of the Greensboro student sit-ins. She went to Miami to challenge segregation in its restaurants, and for her efforts was arrested and placed in a segregated jail. Zellner’s hope is that the stories collected in this volume will inspire others to activism. She notes that just as she grew up hearing stories of people who challenged power and braved the consequences, others may be called to action as well.

These are remarkable true stories from women who at the time were young, old, educated and not, rural and urban, Black, White, and Latina, whose collective actions made a real difference. This autumn through spring 2011, the women of Hands on the Freedom Plow will be making book-related appearances around the country, from Brooklyn, New York to Hattiesburg, Mississippi.

Read the full review at Women’s Voices for Change