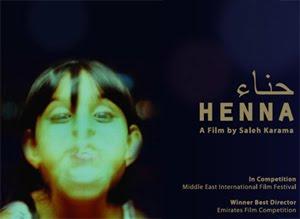

Henna

Henna is a visceral cinematic experience that functions as an exercise in patience. Drawing from reflections on his own childhood growing up in a rapidly developing Abu Dhabi, Saleh Karama created the character of Henna (A’aesha Hamad), a curious eight-year-old girl through whose perspective we are invited to see the world.

Henna lives in a fishing village in an unnamed Arab country. The goings-on of daily life are marked by their simplicity, which is transferred to the viewer by lingering scenes of mundane living: collecting fish that have been caught in nets, conversations over coffee about nothing in particular, the process of cooking lunch for a visitor. At the side of the screen is Henna, eyes wide and twinkling with apt absorption.

The viewer is introduced to Henna on the floor of her bedroom, completing her homework before her mother shoos her to bed. The young girl lives with her mother and grandfather; we are given the impression that her father—who abandoned the pair after Henna’s mother was stricken with an unexplained illness—drops by only once in a while to bring uselessly modern gifts, like bottles of soda.

Most of Henna’s story rests on the visual juxtaposition of contemporary and traditional living. It’s often subtle, as with scenes of gender role segregation where women speak to other women and men to other men; female servitude is expected even as Henna’s family encourages her education. Elsewhere, it’s seen through the lens of infrastructure: The village lacks adequate water for its inhabitants, but the ongoing construction of things like paved roads that camels cannot cross and shopping malls with flashy, expensive goods interfere with the inherited methods of operation that have existed for centuries. When Henna’s uncle Tarsh, a Bedouin man who has been living in the desert, comes to visit, the stress of the newly formed, hurried ways of the community’s impetuous youth are too much for him to abide, and he promptly leaves.

Absent of narrative commentary, Henna leaves the viewer to sort out the benefits and drawbacks of the many different ways of existing in the world and the conflict that occurs at the cusp of change. Using a visually induced melancholy, coarse cinematography, and acting that comes across as more innate than put on, one is asked to consider the paradox of what is lost and what is gained during the process of industrializing the desert.

Originally published in Bitch Magazine