The Heyday of the Insensitive Bastards

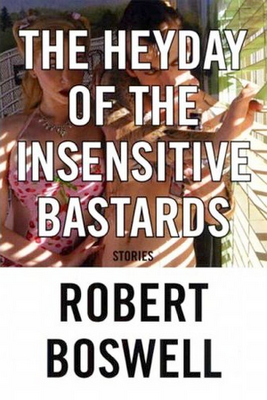

We’ve all heard it a million times: Never judge a book by its cover. And I usually don’t, but when I received Robert Boswell’s The Heyday of the Insensitive Bastards, I judged. The package wasn’t very compelling. It’s as if the author, publisher, or whoever the hell in charge of such things said, “Let’s completely cater to the teenage demographic by naming the book after the only short story in it to include a curse word. And oh yeah, let’s make the cover as completely fucking low budget and Hot Topic-inspired as possible.”

Pictured is a blond in a cherry-printed bikini. Her eyebrows are drawn on, her lipstick is blood red, and she has a look on her face that says, “Come near me and I’ll rip your face off.” Her companion, a baby-faced, tattooed, waif of a man, has a mohawk and is cautiously pulling the blinds open with one hand and holding a nearly empty Jack Daniels bottle in the other. The cover left me wondering what the hell this group of short stories was going to be about.

Given the cover, I was pleasantly surprised by The Heyday of the Insensitive Bastards. Before reading this collection, I’d never heard of Boswell. After some digging I found out he apparently has an affinity for society’s undesirables and Middle America. I too have a thing for freaks and geeks and these pages are jam packed with emotionally stunted, crippled, and horribly confused working class Americans who seem incapable of wanting or expecting anything more from their barely mediocre, sometimes heartbreaking lives.

Aside from the types of people who inhabit the pages, the short stories themselves have no unifying theme. Much of the writing is hit or miss, either dead on or completely over the top. Each tragically flawed character is interesting in their own way, but some aren’t very believable. This, however, is certainly not the case for Father McEwen in “Supreme Beings.”

The priest has a penchant for bourbon and beer, and gets an erotic charge when nearly forced to paddle the bare behind of a teenage girl in front of her mother. It isn’t so much the idea of having a naked, young woman quivering and crying in front of him, but rather the idea of having power over her, and the ability to spank her causes him to masturbate while mentally replaying the scene later on in his room. Eventually, Father McEwen comes to terms with the fact that he’s lost the faith necessary to remain in his current position, but that, of course, occurs after his sordid affair with a married woman.

Many of the stories featured in The Heyday of the Insensitive Bastards failed to move me in any spectacular way. (“A Walk in Winter” is as long, tedious, and meandering as the drive described in its opening paragraphs.) That being said, each story includes a biting observation spliced in, like small truths I found difficult to shake off because they seemed so sad, so uncomfortable, and so like thoughts I’ve had myself.

Take for example the story of Howard Duel in “In a Foreign Land.” He is a fifty-something divorcee who’s found himself in the very uncomfortable position of being the oldest person at a mostly twenty-something hipster party. Everyone’s a writer, everyone’s fabulous, and Howard can see through their bullshit. Surprisingly, he’s not there chasing skirts and looking for a younger replacement: “Like most recently divorced men, I longed for my ex. If you have to ask why, you must be eighteen and of no interest to me.” Well, I’m twenty-four and still intrigued enough to wonder whether or not that’s a common feeling.

The Heyday of the Insensitive Bastards is filled with people waiting on those who will never come back. People hoping for things that will never happen. People longing for things that used to be. People who are so wrapped up in the day-to-day bullshit that they can’t even see how bad things have gotten. Essentially, we’re all reflected in Boswell’s writing. It’s just that sometimes he doesn’t really capture the feeling as well as you’d like. Maybe in the next collection.