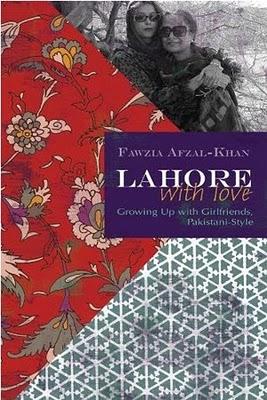

Lahore with Love: Growing Up with Girlfriends, Pakistani-Style

A poet’s power lies not only in her well-crafted images but in the rhythm of her recitation. As I read Lahore With Love, the memoir of Fawzia Afzal-Khan, I longed to hear her read the volume aloud. Many parts of her story poured out in a stream of consciousness, and her anecdotes deftly wove between youth and adulthood, lighthearted desires and the pain of loss, politics and the laughter of girlfriends.

Afzal-Khan interweaves her personal story with key elements in the history of the establishment of Pakistan, her homeland, which was formed just ten years before her birth. The painful string of military dictatorships running her country creates a mirror for the tragic experiences endured by her girlfriends. As she writes, with foreboding, “I have sensed disaster coming their way, my way, my country’s way.” In some ways, Afzal-Khan escaped disaster: she is a professor in the English Department at Montclair State University (New Jersey), a scholar of postcolonial studies, a poet, and an actress. Yet while she lives a successful life in the United States, she carries with her a complicated sorrow and relief, a pain of loss that is aggravated each time she visits Pakistan and sees some new wounds inflicted upon her home and her loved ones.

Lahore With Love gives us vignettes of upper middle class life in a culture where propriety called for gender-segregated social gatherings, but someone was always ready to break rules. The line between acceptable “colonial” habits (Catholic school) and the dangerous “Western decadence” (art school) was at times thin and slippery. As the author forges her own self-identity, the nation also seeks a shape; she heads to the U.S. to obtain her PhD, and Pakistan begins to undergo Islamization, with new layers of reactionary rules added to the old. There is nothing dry about the presentation of material; in one bloody chapter, the story of Shia martyrs is juxtaposed with bullfighting in Spain.

At times I would have enjoyed seeing the vignettes fleshed out more fully, and I suspect some readers will want a volume of Pakistani history by their side to read further about incidents to which the author refers. However, any changes to the unique narrative structure would detract from the author’s intense style. Her voice is the one we use when we long for a reunion with dear friends who are now gone, or hunger to return to the past to stop tragedy from striking, or barely restrain our anger at the callousness of our fellow humans.

Afzal-Khan asks, “Are we doomed to inhabit this binary universe or can we challenge the system that turns us into the roles we wear like selves?” She sets for the reader a powerful mold-breaking example when she self-identifies as “actorsingerpoetactivistmemoirist.”