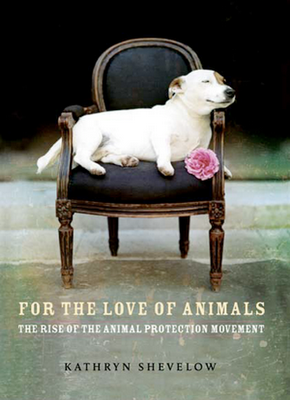

For the Love Of Animals: The Rise of the Animal Protection Movement

Most people seem to agree that on some level, animal abuse is wrong. Whether this judgment is applied equally across species, however, is another matter. One hardly has to look further for modern examples of animal rights cognitive dissonance than the public outcry against Michael Vick’s dogfighting ring. Overwhelmingly, the people most outraged are those who also continue to support factory farm systems that abuse cattle, sheep, pigs, poultry, and countless other animals in the name of convenient clothing, beauty products, and meals.

Regardless of how you justify these contradictions—whether or not you participate in the paradox—a book like Kathryn Shevelow’s For the Love of Animals puts the history behind animal rights into perspective. Using her training as a historian, Shevelow begins in seventeenth century England and teases out the nuances of the last few centuries of animal abuse and animal activism. While you may learn a lot of trivia—that, for instance, the word “vivisection” was first recognized in the 1707 Oxford English Dictionary—the content is by no means trivial.

Throughout Shevelow’s comprehensive account, early animal activists like Margaret Cavendish and Richard “Humanity Dick” Martin are introduced and colorful scenes of early London marketplaces are depicted. Like many accounts of gradual revolution, much of Shevelow’s narrative takes place in the streets, where animals were bought, sold, and beaten. Along the way, as animal cruelty in public ran parallel to the rise of domesticated pets, animals were recognized in humanistic ways. Animal performers—that is, dancing dogs and drum-beating monkeys—served to remind people that all living beings are less removed from one another than we’d like to believe. Animals were taken to court for crimes, and many were found guilty and executed. Even more bewildering, stories of “monstrous births” emerged in the early 1700s. While the obsession of women giving birth to non-human animals eventually died down, even these notably strange events proved that the relationship between animals and humans was becoming inextricably complicated.

Shevelow details the heinous attractions of not-so-distant times: cockthrowing and cockfighting, bullbaiting and bullrunning, dog and horse racing, ratting, and hunting with hounds. Though it’s tough to be objective, I’d like to assume that even the most outspoken, animal-hating carnivore might be disturbed by Shevelow’s descriptions. She also documents that even centuries ago, several prominent observers of animal-based amusements were deeply disturbed by what they witnessed.

She additionally makes mention of many contemporary issues in animal rights activism and vegetarian practice. Citing the story of Dr. George Cheyne, who restored his once doomed health by removing meat from his diet, Shevelow offers historical evidence that plant-based diets can have notable health benefits. There is also mention of religious beliefs that indicate souls moving between species. If you belong to a faith that believes in reincarnation, for instance, you’re less likely to kill animals, lest you become one in a later lifetime.

The book ends with the successful founding of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) in the mid-nineteenth century. As a history text, this one is thorough and happily ends on a victorious high note.

On the other hand, analysis of contemporary activism and food justice movements only receives a frustratingly short two-page conclusion and lacks a lot of analysis about the current state of animal cruelty in the Western world. Praising the efforts of typical figureheads Michael Pollan, Peter Singer, and PETA’s Ingrid Newkirk, Shevelow seems convinced that consciousness and change has advanced as it should. Maybe that’s why she’s a historian and I’m not. For me, progress can never come quickly enough.

It is a discussion of a moment in time, not the movement overall. Her focus is on an era she is knowledgeable about. For those interested in other moments and current history, there are other good sources.

She underlines that much more needs to be done. She is in no way complacent on that front.

Thanks for posting this review. I just bought the book as a result.

Agreed: progress is taking too long, it always does.

Peter Singer is great - but some of his ideas are not so laudable. Same with PETA, as while many of its efforts are effective and honorable, some are downright awful. It would have been awesome for Shevelow to go into this rather than presenting us with one POV alone, particularly when these figures are so controversial.