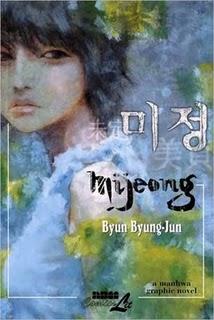

Mijeong

Mijeong is a collection of short stories by Byung-Jun Byun in manhwa form. In a word, Mijeong—a Chinese word meaning “pure beauty”—is moving. No matter what the story (there are seven) I was encouraged to think critically about men and women, adults and children, and their relationships to one another. Although the stories don’t seem to overlap, each is about a young person or young people dealing with the realities of their harsh urban world. Whatever else the author does, it’s clear the manhwa is striving for the beauty the title implies.

“Manhwa” is the general term for comics, print cartoons, and graphic novels in Korea. In other parts of the world, it’s usually marketed as Manga, a Japanese term meaning the same thing. One way it’s certainly different from Manga is that it’s read from left to right—the same direction as books in English—not right to left, as Manga traditionally is.

The author’s artistic style is more realistic than most Manga I’ve read. Characters’ eyes, for example, don’t seem to be a dominating facial feature. The art is more expressionist than I was expecting, and each page seems fuzzy, as if I was reading it through a dream. Most of the stories are in black, white, and grey. The one in the middle, “Song for You,” however, is cast in pastel hues and shows Byun’s artistic progress in the representation of space. Over all, the writing is sparse, letting the art speak except in cases of character dialogue.

I was struck most by “Yeon-du, seventeen years old,” which is about a young woman who acts in a porn film in order to be able to pay for a piece of art that a childhood friend of hers loved. We learn that the friend was killed trying to protect her from rapists at a young age, and now she lives to avenge him.

In “Utility,” a group of friends finds one of the girls' siblings hanging in her apartment after committing suicide. Because they’re afraid someone will come in and think they killed the young woman, they try to decide how to dispose of the body. It is, like Byun’s other pieces in Mijeong, very thought provoking.

This collection is quite an undertaking, and it left me with a sense of Korean urban life as well as the life of young people today. It’s not an overtly feminist collection, but it touches on some serious issues and treats them with respect. I’m looking forward to reading more of Byun’s work in the future.