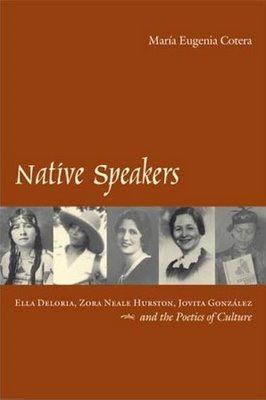

Native Speakers: Ella Deloria, Zora Neale Hurston, Jovita Gonzalez, and the Poetics of Culture

Native Speakers places the work of three foundational female folklorists in conversation to illuminate an often silenced part of feminist intellectual history, the ethnographic and folklore scholarship of women of color. Analyzing the ethnographic and fictional work of Dakota ethnographer Ella Deloria, African American folklorist Zora Neale Hurston, and Tejana folklorist Jovita Gonzalez, the text reveals the numerous factors that led to the marginalization of these three scholars who also happened to be women of color. Exploring how the work of Deloria, Hurston, and Gonzalez negotiates intersections of race, class, and gender in early twentieth century America, Cotera places an emphasis on empire and colonialism. In so doing, she reveals the ways in which imperialism affected colonized peoples in different ways, but led to similar results—silencing, marginalization, impoverishment, forced assimilation, and exile.

Cotera enacts an important excavation of the feminist intellectual tradition revealing that the voices of women of color are not absent as some have assumed, but instead have been neglected or silenced. Emphasizing the need to take historical specificity and social location into account, and arguing that the work of these three women contains "complex decolonizing textual subversions," Cotera further claims that "the most provocative point of connection" is each woman’s exploration of "the political and poetic possibilities of fiction." The emphasis she places on the fictional work of these women is unique, especially in the cases of Deloria and Gonzalez, neither of whose fiction was published during their lifetimes.

The book also documents the history of intellectual theft as it pertains not only to these women of color, but to the work of marginalized "others" in general. This reclamation reveals how various fields (ethnography, folklore, literature, feminism, and so on) have relied on the voices of women of color and other marginalized groups, yet have often rendered such voices invisible by using their work without giving them credit. Illuminating how gender, race, and class play key roles in this socio-historical silencing, Cotera's work speaks volumes about how vital it is to reclaim such histories.

The book is organized in two sections, with the first exploring the ethnographic and folklorist work of Deloria, Hurston, and Gonzalez, and the second considering their fictional work. The text offers a detailed account of the history, politics, and socio-cultural conditions that shaped the work of these three women while offering cogent analysis of how race, class, gender, nation, and empire informed both their work and the responses to it, and is especially useful for those interested in feminist anthropology, ethnography, folklore, and literature.

Bookending the two sections are a lengthy introduction ("Writing on the Margins of the Twentieth Century") and a concluding epilogue ("What Love Got to Do With It?: Toward a Passionate Practice"). Each of these sections are beautifully written with a comprehensive theoretical approach that teases out the complex aims of the text while offering a thorough consideration of the historical, sociocultural, and intellectual traditions shaping the work of these three authors in particular and feminist ethnographers/folklorists in general.

The epilogue is one of the most intriguing sections of the book as it covers what is so often left out in academic manuscripts—love, or what Cotera refers to as "passionate praxis." Drawing on Chela Sandoval’s idea of love as a "decolonizing practice," Cotera argues that the work of these women is both motivated by and about love. Their work is driven, she argues, by a passion for sharing and unearthing marginalized knowledge (in terms of gender and race/ethnicity). Further, their work is about the love(s) of the various peoples/characters populating their writing.

Exploring the role of women as active social agents, these women, Cotera argues, "fundamentally reorient the masculinist and colonialist direction of our collective historical imagination." Exploring what Cotera names as affinities inside differences, their work, along with that of Cotera’s, re-imagines feminist intellectual history, opening up a space for othered voices. What is not to love about that?