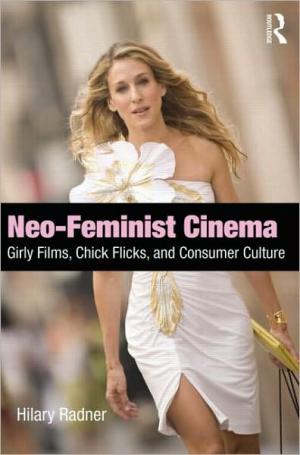

Neo-Feminist Cinema: Girly Films, Chick Flicks, and Consumer Culture

In the past decade, America cinema has shown a change towards producing more women-centered movies, depicting independent unmarried women who seek out their own empowerment and gradually changing society’s view of single women. The women of Sex and the City, for instance, celebrate their singledom, showing it not to be the pitiable state it was once thought to be. While these women possess many feminist qualities, they also have attributes that separate them from the traditional ideals of feminism, a perspective which media studies scholar Hilary Radner labels neo-feminist in her current work, Neo-Feminist Cinema.

Radner compellingly opens her book with a discussion of how neo-feminism differs from second wave feminism. Radner traces the start of neo-feminism to Helen Gurley Brown, who wrote the infamous Sex and the Single Girl. Groundbreaking for its time, the book idealized for women a lifestyle in which they maintained their own independent identities and lives from men, encouraging them to seek out both fulfilling careers and sexual experiences. Through her focus on being fashionable, attractive, and forever youthful in appearance, the former Cosmopolitan editor showed an extreme diversion in her views from that of feminists of the same era, including groundbreaker Gloria Steinem.

In Neo-Feminist Cinema, Radner connects Gurley Brown's views to the neo-feminist views expressed in contemporary works in which feminist-seeming ideologies are undercut by a focus on extreme consumerism (Manolo Blahniks, anyone?) and male sexual attention. Radner then dissects such other modern day films as Something’s Gotta Give, Legally Blonde, Maid in Manhattan, and Pretty Woman. Each films' focus on the girlishness of the characters, regardless of their age (even at forty- and fifty-years-old the cast of Sex and the City possess girlish qualities), as well as women's supposed fixation with fashion and extreme consumerism. Radner posits that neo-feminism replaces consumerism, instead of maternalism, as the primary feminine attribute. Radner’s analysis of each film is both compelling and convincing, though her method of devoting a chapter to each film results in redundancies, as many films possess the same characteristics.

Radner's work is most compelling in her definition of neo-feminism and her historical tracing back to show the roots of the term. Radner gives needed attention to how feminism has slowly filtered into popular culture, mutating the movement into a new form, one that furthers consumerism and maintains a woman’s focus on being sexually desirable to men.

Radner seems overly critical of popular culture in her work. While the neo-feminism expressed in popular works today may be a watered down, shallower version of the feminism second wavers expressed, it nonetheless is a positive step forward for the depiction of women in the media. The depictions of these images encourage women to pursue more self-actualized societal roles and encourages both genders to be accepting of women within such roles. Television shows and films have positively depicted empowered single women for over a decade, albeit ones who may not be quite what our feminist fore-mothers idealized as the future for modern women.

In the end, Radner’s work is both compelling and thought provoking, and she successfully pinpoints the media’s version of contemporary society’s ideal woman. Women who can lead successful and challenging lives absent of husbands and children are positive images to influence women, even if they encourage women to also spend undue amounts of time on their appearance.

I don't understand how anyone could be "overly critical of popular culture"?

What isn't there to be critical of in popular culture regarding "postive role model" women being portrayed, nearly universally, as young, wealthy, thin and beautiful consuming machines?