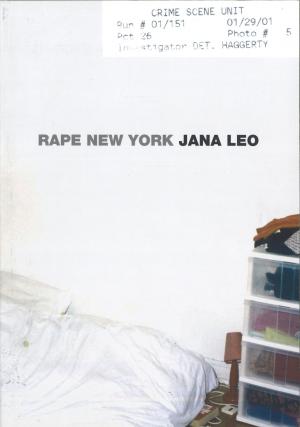

Rape New York

Rape New York: Jana Leo’s title seems to defiantly ask its readers to ‘rape’ New York. It also simultaneously turns ‘rape’ into an adjective with which to describe New York City. Fascinated with this title, I pondered the difference a comma could have made. Rape, New York would then turn ‘rape’ into a borough of the city. This wordplay is not insignificant in Leo’s ultimate argument.

Leo begins the book with a straightforward and chilling narration of the day she was "non-violently raped" by a stranger in her Harlem apartment. The rest of the book narrates not only the six years following the assault but also how she came to live in New York City in the first place, and specifically how she came to live in the apartment in which she was raped. Through referencing place in the book's title, Leo locates 'rape' directly and uncomfortably beside New York, thereby exemplifying her major argument: namely, that (literal and metaphorical) location matters. Gender, poverty, and race are factors that matter in determining who rapes whom and who gets raped. These factors also contribute to one’s relationship to space, and rape and space have a close relationship indeed.

Leo considers the many ways place, particularly the places we identify as 'home', is bound up in the act of rape. Leo describes in great detail her feelings and experience of displacements following her rape. As the rape occurred in her home, Leo has nowhere to go to feel safe afterward—the rape took the security of home away from her. She insightfully considers how most rapes occur in, or in close proximity to, women's homes, and beautifully weaves this together with a critique of home as a female/feminine space.

In her systemic analysis of the factors that caused her rape, Leo focuses on the lack of security in her apartment and how and why dangerous places are both created by and uphold capitalism. She accessibly writes about the deep connections between the low-income neighborhoods filled with people of color that disproportionately fill prisons and how these neighborhoods are the ones that become gentrified locations for urban development—spelling out the way capitalism benefits from poverty and creates high crime areas in the interest of devaluing property that can then be 'developed' by the rich. That her rape occurred in a badly kept apartment on a block in Harlem under the control of a grossly wealthy, philanthropist slum landlord is no accident, explains Leo.

Leo understands the difficult line she walks (and I would argue she walks it successfully) between widening the scope of ‘blame’ from the individual who perpetrated her rape to the wider system of capitalist, racist, and misogynist societal causes. She does not deny the rapist's personal agency nor erase the choice a perpetrator makes to commit rape. In one of her most challenging conclusions, Leo writes, “The fact that rapes relate to poverty, especially the perpetrator’s poverty, makes it, to a certain extent, a default effect of capitalist exploitation and not simply the result of mental illness.” Leo fights the urge to simply pathologize the perpetrator by suing her landlord for his negligent role in her rape by failing to providing a safe and secure building in which rape (and other crimes) would less easily occur.

Leo’s powerful voice and clear minded critique make her a fine guide through the messy terrain of overlapping oppressions and sexual violence. While dealing with complicated intersections, and often adopting an academic tone, Rape New York is an accessible and extremely valuable addition to the conversation of violence against women.

Sam I like your inquiries about the title. Nobody before said anything about it and it was exactly what you said. You are for real a writer and in my view smart too. Thank you for pointing this out. J