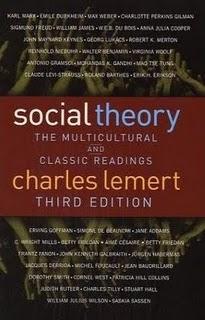

Social Theory: The Multicultural and Classic Readings

The fourth edition of Social Theory: The Multicultural and Classic Readings offers a lesson in sociological practice that moves beyond the atmosphere of a university auditorium. This collection is arranged in chronological order and organizes the Modern Era into distinct historical categories. However, the overarching themes of decentering, discourse, and difference are incorporated into the discussion of each era in a way that is seamless yet meaningful.

Lemert’s expressed goal in creating a comprehensive collection that combines sociological masterpieces with yet unexplored pieces is to simply provide people with the knowledge to live better lives. Social theory, argues Lemert, can bring people power, pleasure, understanding about their social worlds, and most importantly, the ability to put their experiences and observations into words. Social theory thus allows people to explore and express inequalities and social disruption, investigate class warfare and communication breakdowns, and discern how differences between people can be magnified, nullified, or respectfully approached.

It’s especially interesting to read this collection at this point in time. Honestly, it will probably always be considered a reflexive, thoughtful text, but some of the pieces that I read were almost predictive of the current global state of affairs. For instance, in 1919, John Maynard Keynes offered an economic philosophy that recommended state policies which would control and direct the economy. In recent history, conservative talking heads could be heard lambasting “Keynesian Economics,” as the government takeover of the free market. Today, we know that the market doesn’t always stabilize as effectively as Capitalists say it does, and it could be argued that Keynesian Economics seems to be more sensible than Socialism.

The role of women in this collection of essays is hardly marginalized, however, since the writings move from older to more recent, a greater selection of feminist writers emerges towards the book’s end. The feminist selections in this anthology are theoretical yet practical, and seem to focus mainly on the topic of difference. Both social theorists and non-theorists can garner inspiration and motivation from the lessons provided in these pieces. In "The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House," Audre Lorde states that meaningful discourse can help women and other historically oppressed groups to “take our differences and make them strengths.” Likewise, Nancy Hartsock advises that “we can construct an understanding of the world that is sensitive to difference.” Within the context of globalization, Saskia Sassen moves beyond the realm of language and argues that issues of participation and representation should take center stage in current feminist analysis.

Could this mean that globalization is helping the world to become more sensitive to difference? I’m not sure, and they authors don’t say either. But that’s one of the goals of this collection: to make you ask questions and decide on the answers yourself.

Social Theory: The Multicultural and Classic Readings certainly provides readers with an array of arguments that don’t always coincide with one another. However, Lemert’s personal argument to readers can be witnessed in nearly every essay. That is, to think about the social world around all of us. Because by thinking, observing, and expressing our sentiments about this fascinating world, we are using a critical eye, and ultimately, improving our own lives and hopefully, others’ too.