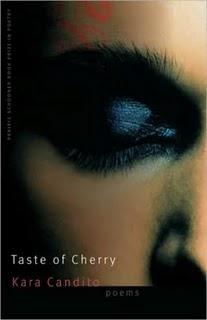

Taste of Cherry

One of the best ways to support awareness and understanding of taboo topics is to display them in a way that is non-threatening and invites discussion. Kara Candito’s Taste of Cherry is just such a collection of poetry. Bringing to life love affairs in everything from Greek myth to the HBO series Carnivale, Candito familiarizes the reader with both bizarre and mundane romantic entanglements. The collection’s chemistry is successful because she isn’t dependent on smut to get her point across: sensuality is skillfully woven in between the lines. (Let the records show that Candito’s poems also have their fair share of deliciously overt naughtiness, however. Not to worry.)

When I say sensual, I mean that in a very literal sense. While there is a certain amount of sex and romance depicted, Candito also uses her work to transmit sensual experiences on many levels. Smell, sound, touch, and taste are used to make the reader think about pain as well as pleasure. Subtlety is a powerful tool here, forcing the reader to draw connections and imagine the effect of cumulative sensory stimulation. The beauty, heat, and uncomfortable truth of each moment are fleshed out in a playful way. The casual changing of narrator gender and ambiguity regarding sexual orientation keeps the reader on his or her literary toes.

The undeniably erotic undertones to this collection of poetry are not to be outdone by political statements and what struck me as ultimatums: Candito presents a situation that is socially unacceptable, describes it as tenderly as she has the rest, and forces the reader to rethink his or her opinions. Women’s struggle between the conflict between society’s expectations and their own desires is an important theme, and part of what makes Taste of Cherry a feminist work.

Another theme is the power of suffering—from self-imposed pain, to accidents, to pain that teaches and heals. This expression can be viewed as an outlet of the female struggle between Self and Other, or perhaps the expression of an issue personal to the author that finds its way into several of the poems.

Whatever the case may be, the strength of this collection lies in Candito’s willingness to state the ugly truth, and somehow make it sound lyrical without losing meaning. Even more intriguing is her ability to pull such a high level of detail from historical accounts, published writing, and Italian opera, leaving the reader wondering how much of her writing stems from personal experience and how much is imagined.