Ten Things I Hate About Me

I was excited when the book Does My Head Look Big in This? came out a few years ago. In that book, author Randa Abdel-Fattah tells the story of Amal, a young Australian Muslim woman who decides to wear hijab and navigates the challenges of expressing her identity as an Australian Muslim. Books about young Muslims in the West (a political and not geographic definition, obviously, given that I’m including Australia) aren’t exactly common, so it’s always exciting when these things do come up.

Abdel-Fattah’s second book is Ten Things I Hate About Me. Unlike Amal, Jamilah, the protagonist of this book, works hard to keep her Australian identity separate from her Lebanese-Muslim identity. At school, she is Jamie, and with her bleached hair and coloured contacts–no one knows that she is Arab or Muslim. The novel takes us through the stress and anxiety that Jamilah faces in keeping her culture and religion hidden, and her eventual path towards finding a sense of comfort to be able to express all elements of her identity.

I’ll say right now that this book is not an especially amazing literary work. The plot is interesting but somewhat predictable. (Fair warning: there are some minor spoilers ahead, but nothing that you wouldn’t have guessed yourself while reading the book.) A lot of the characters are fairly one-dimensional and seem to be there just to make a point: Jamilah’s father immigrated to Australia from Lebanon and has a Ph.D., but works as a taxi driver; her sister Shereen wears hijab (often in the form of scarves decorated with political slogans) and spends all her time out at political rallies and other activities related to social justice. (A religious woman in a scarf who’s really active and vocal? Amazing!)

I guess it’s useful to have these characters there as a way of challenging some of the stereotypes that readers may have, but as Melinda wrote about in relation to Does My Head Look Big in This?, sometimes it felt as if the novel was banging us over the head with its attempts to challenge stereotypes. I would have liked to see some of these characters be a bit more subtle and complex.

That said, the novel still raised a lot of themes that are worthy of discussion and reflection. The story begins with a conversation about the anti-Arab riots that happened on Sydney beaches in December 2005, with one of Jamilah’s classmates (himself a Muslim of Arab background) talking about the injuries he received while fighting against the racist mobs. Some students are supportive of him, while others taunt him, suggesting that the people rioting were right; one student, Peter, complains that “Man, you ethnics and Asians are always complaining... Oh, help me! I’m a victim of racism. The white people are out to get me. Get over yourselves!”

These racist remarks (complicated by the fact that Peter is one of the most popular guys in the school and spends a lot of the book flirting with Jamilah) continue throughout the story. I appreciated that Abdel-Fattah didn’t hold back on describing the racism that Jamilah was facing: it’s not simply a story of multiculturalism where everyone is happy and things like racism are an exception to the harmonious norm, but rather a more raw (and, I would argue, more truthful) portrayal of some of the ugly racism that does exist in Western societies. There is also an argument made about Muslims and Arabs being held accountable for the actions of other people from their communities in ways that other groups aren’t: in one conversation with her aunt, Jamilah argues that:

"When those teenage boys gang-raped girls in Sydney, it was the boys’ Lebanese-Muslim background that was put on trial. I went to school and I watched Peter Clarkson cross-examine Ahmed for a crime he did not commit. I read headlines describing the crimes as ‘Middle Eastern rape.’ I’ve never heard of Anglo burglary or Caucasian murder. If an Anglo-Australian commits a crime, the only descriptions we get are the colour of his clothes and hair.”

Along with this is a really honest portrayal of the effect that racism has on Jamilah. To explain why she hides her background at school, she says:

“I don’t have the courage to be up-front about who I am. I’d rather not deal with people wondering if I keep a picture of Osama bin Laden in the shape of a love heart under my pillow. Call me crazy, but I’m also not particularly excited about the prospect of having to stand accused every time somebody who happens to be of Lebanese background commits a crime.”

This silence, however, takes its toll. When she later talks about another moment where Ahmed stands up against racist comments, she reflects that, “The same prejudice and bigotry that silences me, vocalizes him. And even though my silence protects me, I’m the one walking with my head down.” When the aforementioned Peter tells Jamilah (or, perhaps more accurately, Jamie) that he likes that she is not self-absorbed, she thinks to herself, “”News bulletin: I’m not obsessed with the sound of my own voice because I don’t have a voice. I’m stifling it beneath layers of deceit and shame.” Jamilah’s sense of vulnerability and shame is palpable throughout the novel, and conveys a strong message about the personal impact of racism.

Although my own background is very different from Jamilah’s, there were several moments where I felt that I could really identify with her struggles to juggle several elements of her identity that are so often portrayed as exclusive to each other. Even when it’s not about actually hiding our identities, the fact of belonging to multiple communities that are often understood as separate can be complicated and difficult to handle. The extent that Jamilah goes through to keep some aspects of her identity hidden might seem a bit extreme, but the idea of downplaying certain parts of our identity in certain spaces definitely resonates. Add in the social pressure of high school (which, actually, I did find a bit exaggerated in this novel, but it’s relevant nonetheless) and the need to fit in becomes even more intense. As our protagonist says, “The Jamilah in me longs to be respected for who she is, not tolerated and put up with like some bad odour or annoying houseguest. But it takes guts to command that respect and deal with people’s judgements. Being Jamie at school shelters me from confronting all that.”

Her confusion about how to understand her multiple identities comes out in several places throughout the book. I like the way she illustrates the juggling metaphor here:

“All I want is to fit in and be accepted as an Aussie. But I don’t know how to do that when I’m juggling my Lebanese and Muslim background at the same time. It’s not like juggling an orange, and apple, and a banana. They’re all fruit and all fruits are pretty much equal, right? But the way I see it, juggling Aussie and Lebanese and Muslim is like juggling a couch, a mailbox, and a tray of muffins. Completely and utterly incongruous. How can I be three identities in one? It doesn’t work. They’re always at war with one another. If I want to go clubbing, the Muslim in me says it’s wrong and the Lebanese in me panics about bumping into somebody who knows somebody who knows my dad. If I want to go to a Lebanese wedding as the four hundredth guest, the Aussie in me will laugh and wonder why we’re not having civilized cocktails in a function room that seats a maximum of fifty people. if I want to fast during Ramadan, the Aussie in me will think I’m a masochist. I can’t win.”

As the story progresses and Jamilah’s hold on the strict separation of her Australian and Lebanese-Muslim identities beings to weaken, she begins to realise the effect that this separation has had on her and on her relationships to the people around her.

“All I want to know is what place I have in this country I call home. It all comes down to emotional real estate. Finding your place, renovating it as you go along (a haircut here, a university degree there), and having neighbourly relations with other property owners. So far, I’ve figured that dyeing my hair blonde, poking my eyes with contact lenses, and living a lie at school all guarantee me a share in the Australian property market. But I’m starting to realise how empty my bit of ‘place’ is. It’s got no soul. The cosmetics are fantastic and would look great on domain.com. But you can’t smell life. It tastes like stale cookies and sounds like socks on carpet.”

Cheesy? Well, yeah. And perhaps a bit simplistic, given the racism that was discussed earlier. It’s not as if just deciding to be yourself is necessarily going to make for an easy ride. But the sentiment is interesting, the idea that her attempts at self-preservation in fact become a form of self-destruction and self-silencing, and ultimately prove to be unsustainable.

The personal impact of this silence is also strongly felt at points. Since not a single person at her school knows about her religious and cultural background, Jamilah’s friendships at school remain stunted and superficial, prompting this reflection:

“I don’t have a proper relationship with my so-called closest friend. We’re like the two sides of a train track, each comfortable in our parallel existence. We don’t intersect or touch each other. But sometimes you need to collide. You need to crash and make an impact just to feel your friendship is alive. To feel that it’s more than passing notes to each other in class and sharing fries at lunchtime. I don’t have any collision scars from this friendship. And as deliberate as that is, it’s not something I’m proud of.”

The novel also addresses family issues in interesting ways. Jamilah’s father is very strict with her, and much less so with her brother, who goes out clubbing and drinking. Jamilah’s frustration at this double standard is expressed throughout the book. At the same time, she is very conscious of how this could be seen from the outside, and of not wanting to perpetuate a stereotype of Arab Muslim families as inherently sexist and oppressive. When her friend Amy asks if she’ll be coming to a party, she pretends that she’ll be going, because:

“I’m too embarrassed to tell her that my dad won’t let me go. I don’t want her to pigeonhole me as a poor, pitiful, repressed Lebanese girl. I know that my dad’s strictness is cultural and religious, but I also know it has a lot to do with my mother’s death as well, and the fact that he’s bringing us up alone. I don’t understand him. I don’t always agree with him. But I know that I’m not a stereotype and I’ll do everything in my power to protect myself from being seen as one, even if that means lying to my closest friend.”

The “I’m not a stereotype” idea comes up also in her conversations with “John,” an online friend to whom Jamilah has revealed more about her life than she has to her friends at school. When she mentions that she would be “dead meat” if she ever had a boyfriend (and, more importantly, if her father found out), he responds by asking, “Are you serious? Like those honour killings you hear about?” Jamilah’s frustrated response is to tell him, “No, you space cadet. Sheesh, this is why I hate opening up to people about my family! Can’t I be metaphorical without having my dad equated to a Taliban warlord?”

Okay, so the family stuff isn’t exactly subtle. The book is really clearly trying to make a point that families can be conservative and strict without filling the kinds of stereotypes that non-Muslims might expect. Although the lack of subtlety doesn’t make for amazing literature, I do have to say that the point is a good one, and it’s nice to see something that tackles these stereotypes head-on. Moreover, Jamilah is ultimately able to convince her dad to make small concessions: after some persuasion, she is able to get a part-time job, and after much persuasion, she is even able to go to her school’s formal. I think these changes speak louder than the direct points that she makes, since they demonstrate that her family’s rules are not carved in stone, and that restrictions can be resisted from within, without requiring some kind of saviour from the outside. I’m hoping that readers will understand that, by extension, other cultural rules (and resistance to them) can be equally dynamic, even when they seem monolithic and repressive from the outside.

Religion plays a fairly minor role in the story; Jamilah identifies as Muslim, but this isn’t the focus of the novel (this is actually pretty refreshing—someone can be Muslim while also having lots of other dimensions to her life! Who knew?) Various family members demonstrate different levels of religiosity, which is presented as something normal. Even the hijab is—shockingly—not a major issue. Jamilah’s sister wears it, but it is talked about more as a fashion and political statement than a religious one (although it is acknowledged as both.) There are a few more direct conversations about religion (again with obvious points that the author wanted to convey, like when Jamilah’s aunt argues that, “The Koran has been manipulated and abused to exploit women”), but it was nice to see a story about a Muslim girl that didn’t only revolve around the fact that she was Muslim.

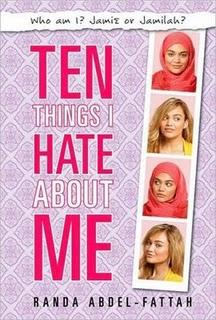

I wasn’t thrilled with the cover of the book. The cover features a strip of photos of a girl, alternatively wearing hijab and not wearing it. This annoys me, because although a lot of the book is about Jamilah trying to balance her Muslim-Arab cultural-religious identity with her Australian identity, she never talks about wearing a headscarf. Her Lebanese culture is talked about in terms of music and food, but not at all in terms of hijab, and it’s annoying to see that on the cover as the representative picture of Jamilah’s Lebanese-Muslimness. Moreover, what does this say about the picture where she’s not wearing hijab? Is that the picture where she’s “Australian”? Can’t she have her head uncovered and still be seen as Lebanese and Muslim as well as Australian? If the whole point of the book is to demonstrate that these identities shouldn’t be mutually exclusive of one another, it seems problematic that there is one way to “look” Arab and another way to “look” Australian.

Overall, while it was often trying too hard to make its points, this book was an entertaining read, and an interesting look into the life of a girl trying to balance her cultures and religion, to cope with the racism and sexism that she faces, and to find a space where she feels at home.

Thanks Julianne! I agree with you about the father. I understand that the author was probably trying to make a point about immigrants whose credentials aren't recognised and so on, and about the many taxi drivers out there who are very highly educated but can't get jobs in their fields, but I thought it was overdone. The narrator did explain at one point though that the jobs available in her father's field were in more rural areas, and the family didn't want to be the only Arabs in a small town, so it seems like that's the reason why he ended up driving a taxi.

I read this recently and enjoyed it, but I agree with all the points you make about it. The repetition of the fact that Jamilah's father has a PhD but works as a taxi driver quite annoyed me - it was mentioned several times without going into why his life turned out like that. Did he find it impossible to get a job in academia because of racism or did something else happen? I really wanted to know and the information was never given.I thought the cover was pretty bad too - the edition I read (UK) actually has a picture of a girl without hijab on the whole of the front cover and a girl with on the back. From this I expected Jamilah to decide to wear hijab by the end but she doesn't. I guess it was a publisher's decision, they thought it was an easy way to signify what the book was about and completely ignored the fact that the images go against the message of the book. I personally think a different, smaller, image on the front and an actual blurb on the back would have been a lot better - I think there was one line on the copy I read! I only knew what to expect from the plot because I'd already read an online description.