Thiefing Sugar: Eroticism Between Women in Caribbean Literature

Tinsley’s fascinating study of “women loving women” examines their colonial and postcolonial experiences in Dutch, French, and English-speaking areas of the Caribbean. This volume, in the Perverse Modernities series by Duke University Press, takes its title from the writing of Trinidad-born poet-novelist Dionne Brand, whose cane-cutter character Elizete uses the phrase “thiefing sugar” to describe her feelings for another woman, Verlia. The metaphor refers to the time when slaves could be whipped for selling sugar from the plantations for any reason; it embodies both transgression and forbidden pleasure. Tinsley points out that using the term is “stealing language itself” to evoke a “transformative desire” to change the status of women and challenge the injustices of society.

Thiefing Sugar: Eroticism Between Women in Caribbean Literature incorporates black, queer, and feminist theory into its analysis. It draws on literature, history, geography, anthropology, economics, and linguistics to paint a colorful, multilayered portrait of Caribbean women. Texts from Suriname, Jamaica, Haiti, Martinique, and Trinidad (along with occasional references to Cuba, Grenada, Aruba, the Bahamas, and elsewhere in the region) are used to explore the history of sexuality and the complications of Creole traditions. Tinsley begins with love songs sung by black working-class women to their female lovers, along with accounts of birthday parties and erotic dances and religious ceremonies, as well as messages exchanged in the symbolic language of flowers, to show the intricacies of gender identities in the West Indies.

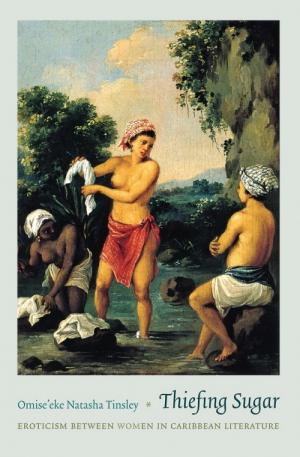

In succeeding chapters she turns to Luminous Isle, an autobiographical novel by the white Jamaican woman writer Eliot Bliss, then to the erotic poems written in the 1920s by Haitian poet Ida Faubert, Mayotte Capécia’s novel I Am a Martinican Woman, Jamaican writer Michelle Cliff’s novel, No Telephone to Heaven, and, finally, Dionne Brand’s poetry collection No Language Is Neutral, in order to trace “their poetics of decolonization” and to point out how these texts suggest reconfiguring gender history to acknowledge the strength and beauty of Afro-Caribbean woman-identified women. Tinsley’s brilliant, sensitive explications, her frequent references to artworks from the area, and her descriptions of lush landscapes make reading her work a delight and a surprise.

However, I do wish that she had studied more than one Hispanic writer, Fidel Castro’s niece Mariela Castro Espín. But I understand that bringing in a substantial number of texts in Spanish would have enlarged her project’s boundaries to perhaps unmanageable proportions. Several references to U.S. interventions in Grenada also left me wanting more information on the effects of North American activities in the region. I hope that Tinsley herself or one of her readers will expand on the groundbreaking work she has done in this book. I highly recommend it to a cosmopolitan audience.