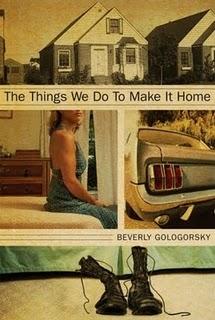

The Things We Do To Make It Home

When Beverly Gologorsky’s powerfully written and beautiful novel, The Things We Do To Make It Home, was first released in 1999, most U.S. residents weren’t thinking about war. The Vietnam conflict had ended decades earlier, the Cold War was over, and for at least a fraction of a minute, world peace seemed possible. Then 9-11 happened, and a world without armed conflict became the stuff of pipe dreams. In short order the U.S. was involved in two wars, fighting what many see as losing battles against terrorism.

This makes the re-release of Gologorsky’s novel especially important. Unlike war stories that focus only on the soldiers’ experiences, The Things We Do To Make It Home includes the lovers and children of numerous warriors—people who have no choice but to grapple with the physical and psychological aftereffects of military life when their loved ones return to civilian life. It’s gripping material, poetically rendered. And, while Gologorsky’s protagonists are exclusively male Vietnam vets, the scenes she conjures will undoubtedly resonate with the family and friends of soldiers now serving in Iraq and Afghanistan.

At the same time, the novel is somewhat enigmatic, offering crisply written and evocative snapshots of post-war life. Much is left to the imagination as Gologorsky conjures reunions and zooms in on the everyday struggles of those trying to re-integrate into late twentieth century New York. In chronicling their experiences, Gologorsky zeroes in on a handful of men whose looming presence forms an austere and ever-present backdrop in the lives of those left behind. As they struggle to plug back into the society they left as eighteen-year-old teens, their confusion and angst never recede from center stage. Now full-fledged adults, their children have grown up without them and the women they once dated or married have become self-sufficient. Small wonder that many see drinking and drugging as their only respite from both present-day realities and memories of serving their country.

At no point does Gologorsky offer judgments about the efficacy of the Vietnam War. Instead, in eight chapters, we meet characters like Sarajo, who at age sixteen wants nothing to do with her now-homeless dad, but who finds herself inexplicably drawn to a photography teacher who spends his days photographing un-domiciled veterans. It’s like a case study in a psychology text, but far more wrenching. We also meet tough-as-nails Lucy, a financially successful professional, whose bravado is fractured by an encounter with one of her disabled husband’s down-on-his-luck GI buddies. Similarly, the saga of Rod, Emma, and their two daughters—the only intact family in the book—adds heft to the emotional sweep that Gologorsky presents.

In a Reader’s Guide to the book, included as an Afterword, Gologorsky describes her goals in writing The Things We Do To Make It Home and says she hopes the novel will make readers appreciate “the travails of women” and give them “a sense of their incredible strength—that is, how much these women give and do; also, the importance of respecting, honoring, and remembering all women whose lives are similar.” The Things We Do To Make It Home does this and then some. It’s a book that sticks with you, literally bringing home the realities of war and vividly conveying the human toll of violence and aggression.