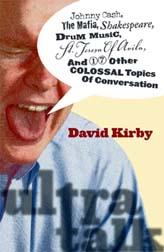

Ultra-Talk: Johnny Cash, The Mafia, Shakespeare, Drum Music, St. Teresa of Avila, and 17 Other Colossal Topics of Conversation

In the introduction to Ultra-Talk, David Kirby writes, “What I offer in these pages is a way to read, see, and savor, a post-theoretical world view that everybody can share.” That is a strong assertion, and though this collection of essays covers diverse and interesting ground, Kirby doesn’t quite live up to his goal.

Elsewhere in the introduction, the author defines a set of criteria for what is “good”: that which “must not only appeal to both the elite and the public…it must also have a track record.” This criteria, presumably, sets the stage for the subject matter he will present in this “book of king-sized cultural monuments.” It is true that the variety of subjects does not disappoint; from Walt Whitman to Saint Teresa of Avila to Nascar to the reality show Big Brother, Kirby delights with his surprising turns and associative logic. Despite his efforts to speak across racial and class boundaries, however, Kirby succeeds in speaking directly, and only, to white, middle-class, academically-inclined readers.

Most of these compositions are a compelling blend of personal essay and literary or cultural criticism; they manage to both entertain and inform, which is a difficult task. Each essay reaches farther than the typical personal essay—start with a hook-y personal anecdote, then move outward toward some larger truth about life or human nature—and attempts not only to contemplate big questions, but also to educate readers in the process. I found Kirby’s explorations of Dante, Whitman, Shakespeare and Dickinson fascinating. But then again, I read those authors extensively during my academic career. Aside from the sporadic, required high school poetry lessons that many teenagers sleep through, most Americans, arguably, have not. By assuming that his reader is well-versed in classic literature, Kirby excludes much of his potential audience.

My point is that Kirby perhaps shoots himself in the foot with the grandiose definition his book presents in the introduction. It’s not that this collection of essays is bad. I, as a white, middle-class, academically-inclined person, very much enjoyed Kirby’s whimsical yet didactic tone and unique perspective on popular culture. The essay “Why Does It Always Have to Be a Boy Baby” was particularly well-crafted in its refusal both to endorse and to criticize religion, opting instead to examine the intrinsic role religion plays in every person’s life, whether or not s/he is a willing participant.

Kirby, a poet and literature professor, is skilled at making intellectual subject matter interesting and accessible. I simply wonder: is his “post-theoretical world view” really one “that everybody can share?”