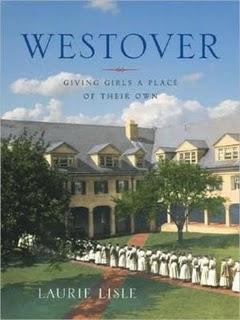

Westover: Giving Girls a Place of Their Own

Few phrases in the English language conjure up more vivid fantasies than the words all-girl school. The education of women—especially in an all-girl environment—is highly political. The ACLU has made the argument that single-sex education has not proven to be noticeably effective, and that it in fact weakens Title IX. There is a constellation of preconceptions that swirl around single-sex education. Many assume that all-girl schools serve as a kind of cocoon and cage, sheltering girls from the real world to their detriment.

So, why make a case for separate but equal schools for women? Myself a former student of an all-girl school, conflicted about my experience, I was curious to read Westover: Giving Girls a Place of Their Own. Written by an alumna, the book is a history of the 100-year-old private boarding school in Connecticut for girls. This well-researched and beautifully designed book tells the story of the headmistresses and headmasters from the school’s founding to the present, closing with an examination of recent debates about single-sex education.

From the very start, women had a voice in the operation of Westover. The school was founded by headmistress Mary Robbins Hillard, a formidable woman and a strong presence in East Coast schools around the turn of the twentieth century. The school was designed by one of America’s first female architects, Theodate Pope Riddle. Thanks to her ingenuity and taste, Westover's gorgeous campus with grounds sprawling over more than 100 acres is now on the National Register of Historic Places. Around the 1960s, a string of male headmasters took the school's helm; however, the current leader of Westover is female, a former math teacher who helped to bolster the science and math curricula at the school.

One of the most interesting aspects of the book is the description of the school's shifting demographics and what caused them. When Westover opened, it was white and socioeconomically homogeneous, with the student body largely comprised of the daughters of the East Coast elite. However, in the 1940s, Westover headmistress Louise Dillingham boldly stated that schools should take a stand on behalf "equality of opportunity in democracy,” and advocated for voluntary integration of the school. The school's board stood firm in their support of the headmistress' statement, though it was controversial at the time. While Westover's progressive pro-integration stance led to declining enrollment, there was an eventual increase in diversity at the school: currently, 21% of the student body is "diverse", per Westover's brochures.

The story of Westover is an engaging one charmingly told, and it gives a good overview of the shifting notions of what makes a well-educated woman throughout the twentieth century. However, when making a case for the continued existence of women's schools into the twenty first century as in the last two chapters of the book, the author—and the heads of Westover—rely strongly on difference feminism—the theory that men and women are fundamentally different in how they communicate and approach problems. I must admit that I'm not entirely convinced by this argument: I feel that all girls’ schools succeed—sometimes—because of more supportive parents, the absence of boys and other factors.

Westover isn't meant to be a scholarly treatise on all-girl's schools and so doesn't succeed as one. Don't read it for a well-balanced look at current debates on single-sex education. Do, however, pick it up if you're interested in the history of American education and possibly its future. To quote current headmistress Ann Pollina, "We need to send out a phalanx of girls who are going to do what the world needs, which is to embody those qualities of care and nurture and community that our culture is desperate for right now. The culture needs our girls." Girls—and not just those at Westover—should take note.