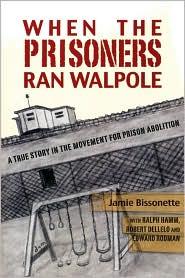

When the Prisoners Ran Walpole: A True Story in the Movement for Prison Abolition

Those of us who spend a lot of time lollygagging in the distant pass frequently encounter scenes of horror — people being tortured for their religious beliefs or identities, for example - and find ample evidence of our capacity for cruelty and inhumanity littering the landscape of human history. The game many of us play to ameliorate whatever righteous indignation we feel as members of the superior present is to imagine what horrors future historians will find in our own generation.

The current administration has single-handedly ushered in a whole host of candidates, beyond the many obvious ones - such as our confidence in the rightful supremacy of our species, which may well turn out to destroy us. Another obvious example is provided by this book and what its authors ominously refer to as the “prison industrial complex.” We can only hope that our enlightened progeny will be able to look back on our penal practices with the same sort of abhorrence with which we now view human slavery. In fact, the authors argue in stark terms, human slavery continues in the United States: prisoners, stripped of their rights and status as citizens, have become the property of the state. The system, they believe, is beyond reform and needs, literally, to be abolished.

Bisonette focuses on an all-too-brief episode of dramatic rebellion and radical change, and she enlists participants in the Walpole Prison rebellion, which began in 1972 and for a brief time transformed a draconian institution in Massachusetts. This historical moment was the result of a confluence of several extraordinary factors; one was the emergence of a strong, idealistic, African American criminologist named John O. Boone, who, remarkably, was given the responsibility (or at least the opportunity), as Massachusetts Commissioner of Corrections, to reinvent a failed penal system - one that was racist, violent, and the worst imaginable environment for human rehabilitation.

Another factor was the creation of the National Prisoners Reform Association by the prisoners themselves, a group that gained negotiating authority in times of conflict, developed programs such as education in Black History that confronted institutional racism and, to a remarkable extent, became self-governing. For a short time, it appeared that incarceration could, at least, be made more humane with work-release programs, education, and inmate participation in institutional governance. The furlough program was another of their innovations. Under Boone, 97 % of the furlough participants followed the rules and were able to make a contribution to their families and their communities. Of course among the 3% was the infamous Willie Horton, made a symbol of racial dread by Lee Atwater and his fellow hatemongers in the 1988 elections.

When the Prisoners Ran Walpole is a sad and exciting book: a very brief moment when some people in positions of power felt that prison reform — or even abolition — was possible and necessary. The book is short of practical specifics in laying out the road to prison abolition, and the polyvocality of the narrative sometimes interferes with the clarity and organization of the book. Still, for those looking for evidence that radical change is possible, the book is an encouraging beginning.