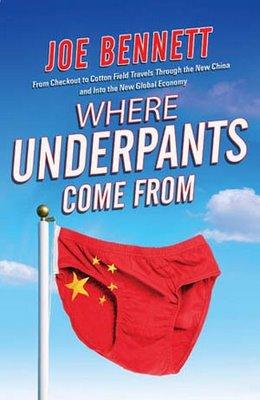

Where Underpants Come From: From Checkout to Cotton Field: Travels Through the New China and Into the New Global Economy

It’s absolutely astonishing to realize how much junk people in North America consume only to throw away. Most of it is from China. When I started to read Where Underpants Come From, I picked up various objects in my office—from the mechanical pencil I write with to my iPod—and I discovered that yes, everything had been made in China. Author Joe Bennett, who is based in New Zealand, does a fantastic job of describing his experience of traveling to that far off land to discover the process of how his cheap underpants were manufactured. The idea is absurd, but he runs with it anyway.

China is the cheapest bidder on manufacturing most of the convenient items we consume at an exhausting rate. It comes as no surprise that the giant nation is, as a result, driving its peasant labor force for meager wages and polluting the air, land, and water at an even faster rate. Statistics aren’t necessary; just take a look at the dirty grey-brown clouds of smog that hover over Chinese cities.

Bennett does more than observe the grainy air; he physically visits various places in China to see for himself what the industrial giant has created in order to keep the Western materialist appetite satisfied. It isn’t pretty, but his encounters are often humorous. As other journalists (such as Anderson Cooper, in the Planet in Peril series) have pointed out, China’s bid to create the cheapest industrial production of everything from underpants to machinery is creating environmental destruction on an astronomical level.

Chinese citizens are also just as disposable. When I was a little girl (in Canada) during Mao’s time, I became interested in not only American Vietnam War veterans, but in the Vietnamese and Chinese soldiers who—as the National Geographic displayed them—were left rotting in dilapidated vet hospitals. Bennett’s descriptions of countless health and safety hazards and substandard machinery show that while Mao may have died in 1976, the view that Chinese workers are easily replaceable has not.

Bennett’s account gets past the stats and much-repeated talk of China as an economic giant. He offers readers glimpses into people’s lives. He goes where the Chinese won’t—places like Urumqi south, where Muslim populations exist—and tries to communicate with the locals. His angle lends compassion and a sincere urge to understand all sides. He admits to his own prejudices against China and its peoples before he actually arrives and notes that people are people everywhere.

As I sit here and type my review on my ‘Made In China’ laptop, the darkness is lit by my ‘Made In China’ lamp, and I drink Chrysanthemum tea (grown and harvested in China) from my ‘Made in China’ glass, I hope that people will take the time to read Bennett’s work. Despite the pollution and slack labor laws and high rate of labor deaths, Bennett finds the people he encounters to be generally happy. Yes, they are driven, but they take time to live for the sake of living and family takes care of family. We Westerners monetarily benefit from the fruits of their hard work, but materialism has only left us miserably wealthy, fat, and insecure.