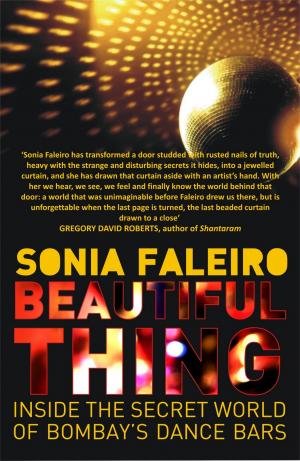

Beautiful Thing: Inside the Secret World of Bombay's Dance Bars

Beautiful Thing is an eponymous title. It is journalist Sonia Faleiro's first book, about the dancers and not-so-secret prostitutes of the “dance bars” of suburban Bombay (Mumbai). These now-illegal establishments offered the tripartite pleasures of alcohol, enticing women, and Bollywood music. Their dancers were “bootiful” young girls, sometimes in their initial teenage years, and well aware that their “booty”—pun unintended—is what defines them, and keeps them fed and clothed.

But this free-market beauty of Faleiro's informants and the women in their lives—mothers, daughters, sisters, wives of their lovers, their hijra (male-to-female intersex, transsexual, or transgender) friends—is what dehumanises them into things. Beautiful things. Things that entertain, things to watch, things to make money with, things to rape, things to give as gifts, things to show off, things to have sex with, things that produce meals, things to punch when the world tightens the screws.

And their eternal tragedy is that their beauty fades, usually by the grand old age of thirty, but their essential thingness, their perceived worthlessness as anything other than beautiful and sexually available women, remains.

And yet Faleiro's informants are neither cowering nor desolate, nor are they subaltern heroines, stiff-upper-lipping the world. Her guide to “the secret world of Bombay's dance bars,” Leela, came to Bombay at fourteen to escape her abusive father's pimping. More infuriating than him selling her virginity to local policemen for a gang-rape at the station, she said, was his refusal to give her the money she earned. Bombay was much better. She could get money just for dancing, relative freedom to choose “kustomers,” and pretty things from men who admired her. Even weekends at expensive resorts. Although the bar owner took the greater share of the money men threw at her, she made enough to live in luxury. If she was forced to "go" with a patron, he was usually a mafia boss, and there was both privilege and profit in sleeping with them.

The histories of the other dancers are all riffs on the same general theme. They come from poor families with too many mouths to feed and little money to do it with. They were prostituted from puberty, and the injustice of being the broke and abused breadwinner nagged them till they decided to start working for themselves in the big city. In their first months several were tricked or forced into brothels, in conditions harsher than home, but most escaped—Leela by jumping out of a window—and found their way to a dance bar. For all the politically-motivated moral outrage directed at these ostensible destroyers of the social fabric and disgraces unto womankind, the bar dancers of Bombay were amongst the tiny minority of poor, illiterate, victims of abuse who managed to win a measure of independence and happiness without institutional intervention, and no social capital apart from their “bootiful” faces.

In fact, if one manages to look past the scene-stealing women, Beautiful Thing is a chronicle of total institutional failure. From “family” and “community,” to the state legislature for banning their “immoral” profession (in open defiance of their Constitutional right to live and work without prejudice), to law-keepers who extort, rape and get free blowjobs from this suddenly-unemployed or illegally-employed demography, these women have been let down by every institutional holy cow. The only place that lends them space—at a price—is the underground nexus of police, politicians and the mafia that “really” runs Bombay. And even then it is a faceless, substitutable existence amongst a steady influx of fresher, younger girls.

Yet, despite the horror, anger, frustration, pity and even guilty relief (there, but for the grace of god...) that one might feel about the dancers, their defining moment comes, fittingly, at the end. Leela, having lost family, job, home, savings, and friends, is about to be smuggled into Dubai without a passport, ripe for every kind of abuse and exploitation imaginable. To reassure a nervous Faleiro, she points to her own smiling face and asks, “Do you see fear?”

And Faleiro has to admit she doesn't.

A beautifully written review, I won't sleep until I find this book! Thanks Priyanka. I think Faleiro belongs on my syllabus for next semester!

Thank you, Chiseche :-) Had we not lived oceans across, I would have been glad to lend you my copy. The book is about SO much more than I could squeeze into this review, that I strongly recommend it to anyone who has even the slightest interest in informal/underground economies and power structures.