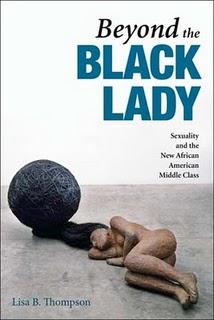

Beyond the Black Lady: Sexuality and the New African Middle Class

In Beyond the Black Lady, Lisa B. Thompson analyzes representations of black middle class female sexuality in literature, theater, film, and popular culture. Her discussions highlight the need to go beyond the “overly determined racial and sexual script” to which middle class black women are expected to conform, which includes a sense of propriety and restraint as a counter to stereotypes of promiscuity that proliferate in the media. Thompson aims to move beyond valorizing black women, with an unattainable (and undesirable) idea of purity, and demonizing black women with assumptions of excessive and inappropriate sexual expression.

For African American women, there is a long history of misrepresentation and a limited menu of options. As Thompson writes, the “intersection of sexism and racism continually undermines black female representation.” In Thompson’s analysis, middle class black women might feel pressure to prove their morality to a critical white majority, while also feeling pressure to prove their legitimacy and belonging to the larger African American community.

Thompson’s scholarship seeks representational strategies that empower black women and subvert dominant stereotypes. She offers examples to illustrate that it is possible to move beyond stereotypes, to embrace a more holistic personhood complete with sexual agency. She offers a lively discussion of Judith Alexa Jackson’s performance piece “WOMBman Wars” as a site of freely expressed sexuality. Through her discussion of independent film, including Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust and Kasi Lemmon’s Eve’s Bayou, Thompson highlights alternatives to the stereotypes of options available to middle class black women in many films. She also includes helpful examples from the genre of autobiography.

Living in a racialized society, according to Thompson’s analysis, middle class African American women might feel a pressure to conform to conventions of propriety and respectability, as an act of responsibility to the African American community and a means to meet familial expectations. However, by leaving conventions behind, we can see more realistic portrayals of women, and women might have a less restricted experience.

This volume is solidly grounded in African American feminist theory, and Thompson deftly weaves in the work of her predecessors. She demonstrates that cultural criticism has a role to play in movements for social justice, because our representations are both fruits of and seeds for representations. With First Lady Michelle Obama in the White House, this book is a timely volume.