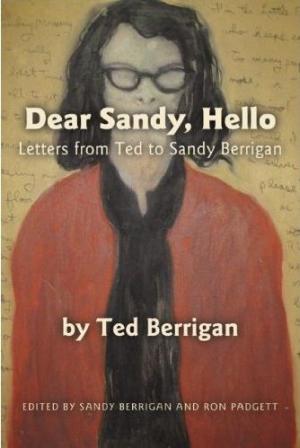

Dear Sandy, Hello: Letters from Ted to Sandy Berrigan

With the post office on the verge of collapse and Facebook statuses eclipsing emails (which not so long ago eclipsed snail mail), I fret for the future of love letters. Decades from now, letters that would have been discovered in a forgotten old box will instead wither away into password-protected oblivion. We will no longer indulge our imagination in the real-life lust and longing of by-gone days, at least not in their raw, unadulterated letter form.

Dear Sandy, Hello is a relic of that (not-so-distant) past when lovers put pen to paper (or typewriter) to express their affections. In this case, it’s a book full of Ted Berrigan’s daily missives on love, life, and literature to his wife and muse, Sandy Berrigan.

Dear Sandy, Hello is also a testament to the (also not-so-distant) past when a woman’s sanity was regarded in direct proportion to her obedience. Just days after Sandy’s marriage to Ted, a struggling-artist-cum-gifted-poet, she is forced by her parents to enter a mental hospital on the basis that “on the date of the marriage she was deprived of reason and incapable of exercising rational judgment.”

It was the uncomfortable awareness that it was a mere thirty-something years ago when a woman could be institutionalized for marrying the man of her choosing, alongside my fascination with the dying art of letter writing, that drew me to Dear Sandy, Hello.

The book opens with a telegraph dated February 13, 1962 from Ted to his friend Joe Brainard: “I was married today at two o’clock in the afternoon to Sandy Alper of Miami Florida. She is nineteen. I am twenty-seven.” A letter addressed to “My darling Sandy” immediately follows—and there begins three months worth of “Letters from Ted.”

For those who do not know Ted Berrigan, as I didn’t before reading this book, he is a prominent figure in the New York School of Poets. That is, he is the poet equivalent of a Jackson Pollack. He is most widely known for a collection of poems called The Sonnets.

His letters document the emotional ups and downs of two lovers torn apart in the height of their lust. As days pass, Ted shifts from zen-like compassion, insisting “that even those who seem to be hurting you love you... that is why I can bear them no malice,” to unforgiving, cold fury. Although written in reference to the specific injustices of their separation, the letters persuasively and poetically articulate a more general struggle against the majority that is hostile to the unconventional. Ted likens himself to Henry Miller and others—artists who resist comfort to be more alive and who ultimately are the “true prophets of the future.”

“Sandy’s Letters to Ted”—amounting to forty pages as opposed to his 200—only appear, incongruously and as though an afterthought, at the end. I read Ted’s letters with a nagging sense that I was missing something, and in the end I wished it’d been left that way. The Sandy of my imagination was more nuanced and intriguing than the woman captured in a few scant letters.

Whether professing his undying love, railing against society, or recounting the most recent book/museum/poetry that he’d explored, Ted’s letters flow as poems do—a web of vivid imagery and thoughts, impressions superseding logic. Taken as I was by the writing, ultimately I couldn’t stomach his artistic hubris overshadowing her injustice.