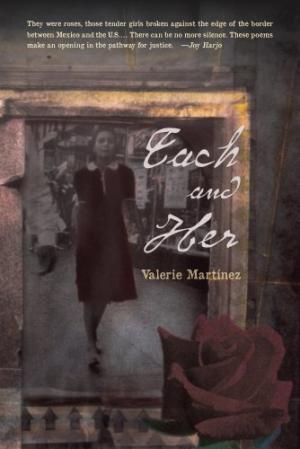

Each and Her

It can be easy and convenient to forget facts learned and impressions made about our southern neighbor, Mexico. Because I like to think of myself as conscious and conscientious of both international news and poetry, I was surprised by my recent discovery of Each and Her by Valerie Martínez. A widely anthologized poet and former poet laureate of Santa Fe, Martínez has been recognized for a career’s worth of community outreach and education, and even for translating Uruguayan poetry.

On the back cover of Each and Her, Martínez’s mentor, Joy Harjo, admires the poet's elegance, metaphor, and noble purpose: “They were roses, those tender girls broken against the edge of the border between Mexico and the U.S. They were our sisters, our daughters, our nieces, granddaughters; they are us… There can be no more silence. These poems make an opening in the pathway for justice.”

I must agree; this is one of the most lovely and thought provoking elegies I have read in a while. Martínez bestows a quiet honor on the lives of nearly 500 victims (since 1993). She does this by encompassing their names in her larger meditations on the cultivation of roses, and on representations of cultures that value (or devalue) those who are vulnerable, female, and poor.

Each and Her is, essentially, a book-length poem; there are seventy-two numbered, title-less meditations that follow a starkly written introduction to the paramount problem: many females, often students or factory workers, have been (and continue to be) murdered in or around Juárez and Chihuahua, Mexico. Martínez’s objective, page-long prologue tells us that the murders are linked by evidence of sexual violence, torture, or mutilation, and that the numbers each year are steadily rising (from twenty-eight in 2004 to eighty-six in 2008). The problem is getting worse, and in its background we see a drug and labor trafficking culture, and exploitation in the maquiladoras, the export assembly plants where some of these girls are employed. In one of her many numeral-rich poems, Martínez cites the number of girls and women who currently work in that industry:

472,423

while they can be hired legally

at the age of 16, it is common for these girl-women

to get false documents

start work at 12, 13, 14

Martínez arranges beautifully sparse facts next to rich details that mesmerize with their quiet reality (“Amalia went back to Juárez / dirt floors/ sheets for doors/ Coca-Cola in small bottles/ in wood crates stacked/ bundles of tortillas and tamales/ out the front window/ pesos and dollar bills/ crushed on the ledge”). Moments like these, and small poems like “this / way” or “I refuse” helped me contemplate the horror (“right breasts severed / left nipples bitten off”) while holding onto glimpses of how these women and girls may have lived before they were tortured and killed (“crush of the crowded Juárez market / Malia is first / hand clutching mine/ Grandmother behind / tethered to Mom”).

I admired how Martínez incorporated found poems, such as selections from the Orthodox veneration of the Virgin Mary and Eve and “the missive / from the attorney general / of the state of Chihuahua,” into the same long poem as her narrated lesson on worthy ancient women: “finally, a great throng of women deserving to be named, some as Greeks, some as muses, some as seers, for all were nothing more than learned women held and celebrated…” Whether suggesting the beauty and toil of flower harvesting labor, evoking the motif of sisterhood, or considering the working conditions of women, as in poem "36." (“a typical maqui working schedule/ 60 hours per week/ typical daily wage—$8.29”), Martínez left me amazed at the breadth of her careful poetry.

The emotion of each experience—of a girl-woman and her loved ones—is nodded to and transcended. Martínez understands that the deep icon of the rose radiates out from what mathematicians or ethicists can understand about these brutal murders. I was literally propelled through these poems by a need to privilege these lives with my attention, by a kind of reverent curiosity about these girls’ and women’s stories, and by the utter pleasure of Martínez’s lovely, sparse, and thoughtful language. Justice often comes through awareness and empathy, and the way that Valerie Martínez reverently and tenderly handles her collection of meditations about this terrifying cultural pattern buoys the possibility of justice, and hopefully, a remedy.