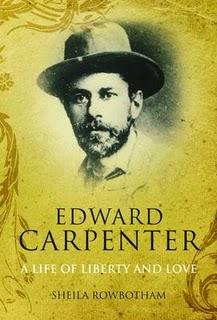

Edward Carpenter: A Life of Liberty and Love

Writing a biography is tricky terrain, particularly on a subject whose name is generally unknown. The author likely has reams and reams of information gathered from years of research and has the thankless task of deciding what can go into the book and what should be left out. For this reason, many biographies suffer from too much or insufficient information. Luckily, Sheila Rowbotham navigates these waters easily with skilled contextualization and engaging writing.

Edward Carpenter: A Life of Liberty and Love takes us through one of the most intriguing periods in Western history. Born to a wealthy Brighton family in 1844, the young intellectual eventually headed off to Cambridge to study theology. However, he was soon swept up in the counter-culture of emerging socialism and class revolution. Rowbotham mirrors Carpenter's growing social awareness with his own "deviant" sexuality with skill and sensitivity.

Shunning his inborn privilege, Carpenter sets off to live an activist life, educating the working class and living off the land. Of course, problems arise. The many strong personalities involved in the Victorian social reform movement made creating an English utopia an impossible task and the affable Carpenter was often left stuck in the middle.

What is most striking about Carpenter's life, and the lives of those around him, is how unexpectedly progressive these individuals were. Almost a century before Greenpeace and recycling programs, Carpenter espoused the importance of eating locally-made food and even the benefits of vegetarianism. Several of his friends lived openly (to a degree) as homosexuals and Carpenter himself had intimate male relationships his entire adult life, eventually settling down with George Merrill for almost three decades.

Full of a genuine desire to make the world a better place, Carpenter and his colleagues all attempted to enact their beliefs to some degree. There was formidable opposition: George Orwell openly despised Carpenter, and around the time of the the trials of Oscar Wilde, both Carpenter and Merrill were the target of witch-hunting conservative groups out to punish homosexuals. But none of this seemed to hold Carpenter back; he continued to publish texts, give lectures, and travel around the world for all of his long life.

His tale is inspiring but also worrying; a century later we still struggle with the same issues Carpenter tackled. Groups like the Fabian Society and the Social Democratic Federation believed a cultural revolution was imminent, and that sexual, gender, and class liberation would occur within their lifetimes. Sadly, subsequent generations have not done these pioneers justice.

Pessimism aside, this book has much to teach us about what it takes to change a strongly traditional culture. Although names like Carpenter's have been lost in the selective retelling of history, the impact that these people's lives made was evident in the cultural upheavals of the 1960s and, one might argue, in activism of the present. An unwavering commitment to a simple, open-minded life made Carpenter an extraordinary person and an inspiring role model.

Rowbotham's biography is lengthy and thus might turn off some potential readers, but so much of the book is about the context of Carpenter's life and the bizarre (and often entertaining) company he kept, which makes the biography consistently engaging. My only criticism is that, as someone familiar with Rowbotham's work, I was hoping for more of a feminist analysis of Carpenter's ideas, as he was close to several "new women" of the day and also a strong supporter of suffrage and women's rights. All in all this is an amazingly written biography!