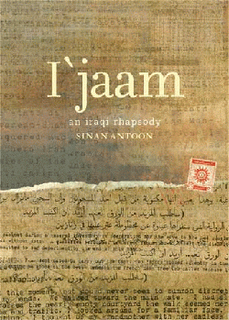

I’jaam: An Iraqi Rhapsody

Sinan Antoon’s novel I’jaam: An Iraqi Rhapsody brilliantly portrays the complex impacts of political repression on humanity. It takes the form of a fictionalized compilation of interpreted handwritten prose of an Iraqi college student as he is held and tortured in a prison during the reign of the Ba’th regime in the 1980s. In the introduction of the novel, the reader is told that the Ministry of the Interior in Baghdad came across a handwritten “un-dotted” manuscript that an individual has "clarified" by dotting and inserting diacritics. Antoon points out that half of the twenty-eight letters in the Arabic alphabet are pairs or triplets with the same skeleton. They indicate different sounds by the varying number and location of “dots” above or below the letter. The word “I’jaam,” found in the title, literally means the “dotting” of Arabic script, but has come to signify something that produces a “clarifying” effect. And, thus, Antoon sets up the prose as "found text" written by a prisoner that government personnel have interpreted and made available to the public.

Antoon’s introduction is remarkable in its ability to blur fact and fiction and encourage the reader to become conscious of the politics of memory, story and interpretation. The reader wonders throughout: What meanings have disappeared or changed because of the “dotting” of the script and the political motivations of the interpreter? Which of these prisoner’s memories are true, and which are hallucinations of an under-fed and tortured captive? Most importantly, Antoon propels the reader to question their own need to distinguish between fact and fiction. He illustrates that life under a repressive political regime often means the inability to differentiate between reality, fiction, time and space.

Antoon writes with an illustrious and brash poetic style that moves the reader in profound ways. We not only understand, but feel the fear, frustration and helplessness that come to claim every inch of an oppressed person’s existence. “To live here means to piss away three quarters of your life waiting,” he writes, “Waiting for things that rarely come…waiting so long that you drown in time, because time itself is a fugitive citizen, trembling with fear and stumbling on the sidewalk, only to be pissed and spat upon by a merciless History.” It is not difficult to read passages like this, which were written in the context of the Ba’th regime, and apply them to the current U.S. occupation of Iraq. The passing of time has only increased the relevancy of this text to current political crises.

The real brilliance of this novel comes from Antoon’s ability to illustrate the tense relationship between culture, history and oppression with subtlety and potency. The narrator struggles to keep his passion for poetry and literature alive as the government attempts to regulate which forms of expression are acceptable and which are not. His obsession with the banned Iraqi poets al-Jawarihi and Muzaffar al-Nawwab illustrates oppressive regimes’ ability to deaden the humanity of the people. Ba’th party slogans and sayings of Saddam Hussein are interwoven with personal experiences and demonstrate the discrepancy between the rhetoric of the regime and the reality of life in Iraq. Ultimately, Antoon’s poetic expression of this dichotomy is his greatest strength as he powerfully unearths the deadening impact of oppression.