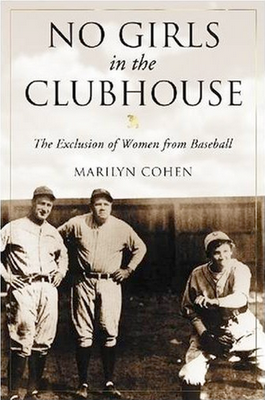

No Girls in the Clubhouse: The Exclusion of Women from Baseball

The premise of No Girls in the Clubhouse is that baseball could be successfully gender-integrated at all levels with no disadvantage to either side, but social expectations—not biological deficiency—exclude women from full participation in the sport. Feminists won't be surprised to learn how, in anthropologist Marilyn Cohen's analysis, the historical achievements of female baseball players have been obscured. Cohen writes that harassment, stereotyping, and social isolation have pressured women to stay out of baseball, while stigmatizing those women who do play. It is an old story, repeated in every designated male realm women have dared to enter.

Yet it is heartening to see this story told by a scholar as sharp as Cohen, and to find that the book's premise—intuitively felt by radical feminists—has the support of history and baseball professionals. No less than Hank Aaron, quoted by Cohen, asserts, "there is no logical reason why [women] shouldn't play baseball," a game that relies on timing and coordination, not pure physical strength.

Part I of the book tackles the history of female professional baseball players. These include Jackie Mitchell, who struck out Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig in an exhibition game; Toni Stone, Mamie Johnson, and Connie Morgan, who played major league baseball in the Negro American League (NAL); and Julie Croteau, the first woman to coach men's college baseball, who played on a winter league team. Cohen also devotes a chapter to the WWII-era All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL)—popularly known from the film A League of Their Own—as well as a chapter to the barnstorming Bloomer Girl teams of the decades before. These working-class teams, usually all-female except for male pitchers and catchers, played against male teams. Cohen cites male supporters of female baseball, like promoter Bob Hope (not the comedian), who in the '80s and '90s attempted to field an all-female minor league team that would play in the men's leagues.

Rather than chronicling an alternative herstory, the book's goal is to analyze the social world of female players—relationships to teammates, coaches, fans, opponents, and the media—and the construction of gender identity. Cohen is sensitive to race and class as well, factors that allowed some women to play while excluding others. The all-white AAGPBL did draft fair-skinned Latinas, but ignored black prospects like Stone, Johnson, and Morgan. Racial integration temporarily opened doors to these women, as black male players signed with Major League Baseball, and Negro American League teams sought new ticket draws. But both the AAGPBL and the NAL folded in the '50s, effectively closing professional baseball for women—the unfortunate outcome of dividing marginalized groups.

Part II is devoted to amateur baseball, inextricably linked to professional, as Cohen shows. Today, Little League teams are often gender-mixed—legally required by Title IX—but with puberty girls meet social pressure to switch to softball. Differences in field dimensions, ball size, and pitching mean that softball demands different skills. The result is that young women who want professional careers, groomed as softball players in their formative years, are disadvantaged beside young men who have had five to ten more years playing baseball. This deficit in skill-development, Cohen writes, accounts for a lack of qualified professional female baseball players. With the same training, some women surely could play co-ed baseball at every level—a provocative suggestion in a book well-worth reading.

Great review! I played baseball/softball for over a decade while I was growing up and our softball team was always kicked to the curb in comparison to the guys' baseball team. I can't wait to read this book! Thank you for your insight.