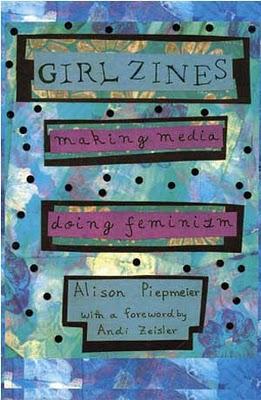

Girl Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism

In Girl Zines, Alison Piepmeier elegantly chronicles the emergence in the early 1990s of zines: a complex, multifaceted phenomenon aligned with third wave feminism, and a powerful and unruly articulation of the same cultural moment that produced riot grrrls. It may also have been the last gasp of the manuscript culture—since, some would say, eclipsed by the blogosphere and electronic media—as a pervasive form of underground radical expression. This study skillfully employs post-structuralist feminist theory, along with the implicit collaboration of the author’s students—generations of whom have been rediscovering the excitement and raw force of these documents, adding their own interpretive spin, and reproducing the zine in their own cultural moments.

She traces the rough avant-garde artistry of Tobi Vail in her work on Jigsaw through well-established magazines like Bitch and the literally thousands of feminist blogs that have established themselves in cyberspace. She traces the origins of such zines as Sarah Dyer’s Action Girl Newsletter back through the mimeographed feminist manifestos of the mid-twentieth-century, and even back through women’s scrapbooks made in the nineteenth century and preserved as a deceptively rich collage of women’s interactions with their cultural milieu.

Girl Zines conveys the brazenness of the zines, their “rhetorical excess and flamboyance” still outrageous and shockingly liberating. A wonderful example, “The Splendiferous Oath of Riot Grrrls Outer Space,” illustrates the tone: “I riotously swear to rage in glorious anger against everything that even slightly pisses me off. I swear to be loud, vulgar, obnoxious, illogical, and emotional whenever I damn please. As an Outer Space Riot Grrrl I will dream of impossible utopias, make up wild political theories, laugh at people who oppose me, and as much as I can, be full of supreme confidence and hellacious egotism.” The loud ripping sounds you hear are conventional gender expectations and forms of institutional oppression being torn to shreds.

Significantly, Piepmeier emphasizes the importance of the materiality of these artistic/political forms. Their textuality—the rebelliously crude printing and the hand-drawn visuals—conveys meaning. They are ephemeral—they share that feature with almost all newspapers and magazines from the time of their invention—but they are nonetheless tangible artifacts capable of being preserved, handed down, revisited, and revitalized. This materiality differentiates them from the creative work being done in the blogosphere, and it is a feature that still appeals to students newly introduced to them as physical representations of a spirit linking generations of women.

One wonders what these radical artists would make of finding themselves within the fairly conventional confines of a scholarly/academic history. And yet, clearly, they have generously supplied both material and narrative to the author, as she inscribes a thoroughly researched, tightly written, and highly respectful account of this phenomenon that needs to be a living part of a developing feminist legacy.